images courtesy of Warner Bros. & Pinewood Studios

Superman:

The Movie at 40;

How it Changed Our View of

Super Heroes

| published March 1, 2018 |

By R. Alan Clanton,

Thursday Review editor

The constant and never-ending reinvention and rebooting of the great comic book and graphic novel themes has become central to the Hollywood business model—so much a part of the machine that we actually give it very little thought, and so generationally constant that it sometimes eludes the youngest of moviegoers that there was a time when the big screen wasn’t considered particularly fertile ground for the purposes of turning super heroes into movie ticket cash.

The recent release of Black Panther, one of scores of Marvel comic characters come to life on the large screen in recent years thanks largely to the power and breadth of special effects and digital composition, reminds us that each major comic retelling has the potential to outperform the previous, with no end in sight. Black Panther has already, within only a few weeks, broken scores of box office records, and spring is not even here yet—this summer will feature still more films based on the exploits of characters from the dueling galaxies of DC and Marvel. Batman film incarnations now number into the dozens, with the arguments over who has been the best on-screen Batman (aka Bruce Wayne) bearing a strange resemblance to those endless arguments over who had been the best James Bond (see a half dozen Thursday Review articles on that topic).

In the world of Gotham fans, there are those who prefer the cool gravitas of Michael Keaton, those who advocate for the brooding good looks of Val Kilmer, those who believe in the strength and grittiness of Christian Bale, and indeed there are plenty who now reluctantly accept the Ben Affleck version. Few seem to agree that George Clooney ever deserved the role, and those of an old enough TV generation still can’t get over their deep-rooted love of Adam West. Everyone has an opinion, just as everyone has a preference for their favorite Joker (I give high honors to both Heath Ledger and Jared Leto, each of whom has made the role very much their own; but let’s face it: has there ever been an actor more born for the part of The Joker than Jack Nicholson?)

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of what can be arguably regarded as the start of the contemporary fascination with the great characters of the comic book world, and the release of a big-budget blockbuster movie which (thanks to its success) opened up a wide highway for the big screen reincarnation of the super hero—a realm previously limited to low-budget television and even lower-budget Saturday matinee shorts.

Superman: The Movie (also frequently referred to as simply Superman), released six months behind schedule and millions over-budget in late 1978, was a massive risk; at that time it was the most expensive motion picture ever produced. At a cost of more than $58.4 million even without advertising and marketing, its ability to succeed may have been seductive, but its power fail was even more visceral, carrying the very real risk of triggering bankruptcy for the studio and the inevitable series of lawsuits which follow such catastrophes.

But succeed it did, with a vengeance—not only financially through its immense box office draw, but also critically, establishing its place among not only the biggest moneymakers in Hollywood history and affixing its place in the pantheon of dynamic action adventure tales and winning the kudos of otherwise credulous film reviewers. Superman also paved a wide path for the future, opening the door to what now seems an endless procession of big budget movies based upon the classics of the American comic book hero from the archives of both DC and Marvel. Had Superman: The Movie failed, its ignominy may have spelled the end of such adventures—there may have never been a big screen Batman, no X-Men, no Avengers, therefore no Captain America nor Iron Man, no Hulk nor Spiderman, no Wonderwoman, no Thor, no Black Widow, no Falcon. Likewise, no big screen Mystique, no Magneto, no Professor X, no Storm. And so on.

When the first talk of a major Superman movie was moving about within Hollywood circles in the early 1970s—not long after producer Ilya Salkind first settled on the idea of a Superman film—the chatter ranged from the sublime to the simply absurd. Among those A-List actors strongly considered for the part of the Man of Steel: Dustin Hoffman, Muhammad Ali, Steve McQueen, Burt Reynolds, even Neil Diamond. But a basic problem immediately ensued: any actor with appropriate physique bore zero resemblance to the Superman most closely associated with our comic book images. Those few with a passing resemblance bore nothing in common with the physical attributes—muscle mass, height—needed; Robert Redford, for example, who flatly passed on the offer; Kris Kristofferson, who was deemed too craggy and lined; James Caan, flush off success in The Godfather, who passed on the prosthetics and the goofy suit. Literally none were willing, or so they said through their managers and agents, to endure the kind of body-building and training necessary. Those willing fell far beyond the range of what would work in any practical sense. Arnold Schwarzenegger, still relatively unknown outside of body-building subculture, was briefly considered, but an American super hero with an Austrian accent was deemed inappropriate, and schemes in which his lines with be dubbed-in post-production (using the voice of Jon Voight, or Lyle Waggoner, or even Charles Bronson) quickly collapsed. George Hamilton was deemed a likely match, but he was neither seriously offered the part or he declined. Likewise, rumors of James Garner being offered the role came to nothing.

Further Godfather connections complicated the issue. The version of the screenplay chosen very early in development had been written and rewritten by novelist Marion Puzo, a gifted storyteller and powerful writer. Puzo was paid a reported $600,000 to write the first major Superman screenplay. But Puzo’s script ballooned to an improbable 550 pages by the time backers had settled on Richard Donner as director (this, after original director Guy Hamilton, working with Puzo’s massive script, had already started attempting to film some flying segment and special effects scenes in Italy, much to disastrous effect; more than $2.5 million was spent on various flying contraptions, aerial gimmicks, and space travel sequences, the footage of which became an embarrassment to Warner Brothers and Columbia Pictures). Besides, the only major actor hired by that date—Marlon Brando, who was to play Superman’s father Jor-El—could not set foot in Italy due to an outstanding arrest warrant.

Planning, development, shooting, and any semblance of progress were all put on hold while a variety of complex negotiations proceeded. There were more searches for actors to play Superman/Clark Kent, and at least a dozen other writers got involved in script development.

Finally, in late 1976, Richard Donner officially took on the role as director after others turned it down or found themselves immersed in other projects. Steven Spielberg, already successful from Jaws, was deeply involved in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Others were considered, including George Lucas, Peter Yates, Sam Peckinpah, Francis Ford Coppola, and William Friedkin.

When, in 1977, Donner took one long look at Puzo’s ungainly, unwieldy screenplay and tossed in into the trash, he decided that the entire project—script and all—needed to start afresh. Donner decided that the campy version of Superman was out; in its place would be a semi-serious, at times melodramatic tale, deeply rooted in the long comic book ethos and mythology of Superman and its strangely American yarn. So while Donner and new writers took on the task of developing the great big screen reboot of Superman, the search began new to find the right person for the part.

Enter Christopher D’Olier Reeve, a New York City born, Princeton Day School graduate who chose Cornell as his college. Unknown in the middle 1970s aside from some stage and theater roles, as well as a later minor role in the 1978 military action film Gray Lady Down (about a submarine which loses power and sinks), Reeve was friends with only one or two actors of notability—among them Katharine Hepburn, William Hurt, and Robin Williams. But during his college acting days, Reeve had met an agent by the name of Stark Hesseltine, who represented such names as Robert Redford and Richard Chamberlain. Hesseltine saw something in the tall, handsome Reeve, though at the time he was not certain to what end those looks would prove profitable. A few years later, hearing of the frantic, even at times absurd search for the right actor to portray Superman/Clark Kent, Hesseltine contacted Reeve in 1977 and suggested—indeed insisted—that the young, athletic American actor contact casting director Lynn Stalmaster.

According to Hollywood legend, Stalmaster immediately knew that Reeve was the right actor for the part, and attempted repeatedly insure that Reeve’s portfolio and resume remained in the number one position. But the studio chiefs and producers were unconvinced, concerned that Reeve’s lack of star-power would inhibit the movie’s box office strength—an unknown in a major big budget production, thus sabotaging the film’s ability to be taken seriously by the public or the critics. With the cost of filming sure to balloon into the tens of millions, Reeve in the lead spot was considered a pivotal risk. So hundreds were given the chance to audition, some well-known, others not-so-well-known, with Reeve's name remaining low on the list.

Finally, after more A-List actors either turned down the part (Paul Newman was reportedly offered $4 million for any of the major roles, including Superman or Lex Luthor) or were rejected as simply inappropriate for the part (discussion of Steve McQueen or Charles Bronson, both major box office draws, were rejected for obvious reasons), Reeve was offered a bona fide screen test...only a test...for skeptical producers and director. According to those present he nailed it on the first run-through, offering a dazzling interpretation of the dual characters of Clark Kent and the Man of Steel. Amidst much reluctance and uncertainty on the part of Donner, Salkind and others, Reeve was offered the part, but was asked to undergo fitting for a variety of cumbersome and complex prosthetic devices and foam pads to simulate Superman’s immense muscle mass. But Reeve demurred, insisting that he be given the chance to gain genuine muscle tissue in order to play the part on the level, as it were. Working with British body builder and actor David Prowse—known for being the hulking, imposing body inside Darth Vader’s black cloak and helmet, James Earl Jones being only the voice—Reeve, who stood 6 foot 4 inches, went from a rail-thin 179 to a substantially beefier 215. Prowse’s exercise and body-building program continued right into principal filming, this insuring that Reeve would continue to gain muscle mass and retain his new-found physique.

Meanwhile, other casting decisions were finalized with much success. Brando’s role as Jor-El was secured, though the high-maintenance actor demanded that his shooting take no more than 12 days total. Gene Hackman was given the plum role of chief villain and Superman nemesis, Lex Luthor. Ned Beatty was cast as Otis, Luthor’s devious sidekick, and Glenn Ford was chosen to play Jonathan Kent, Clark Kent’s father. Jackie Cooper was cast as Perry White, editor of the newspaper, The Daily Planet, which would later employ the young Kent. And Margot Kidder was cast as Lois Lane, an ambitious fellow reporter who would soon become a love interest for Superman. Other A-list names of stage and screen were also brought into the fold: Trevor Howard, Jack O’Halloran, Terrence Stamp, Susannah York, Maria Schell, Valerie Perrine, and Marc McClure, who plays the young photographer and budding reporter Jimmy Olsen.

While all these machinations were at work, various writers—among them David Newman, Leslie Newman, Robert Benton, and Tom Mankiewicz—were rebooting the cumbersome Puzo script, detoxifying the campiness, extracting the silliness, and attempting to refocus the monomythic story into its own unique narrative, a film which would be sometimes serious, sometimes romantic, sometimes comic, but more balanced and approachable than Puzo’s immense work. Finally, after months more work and with a screenplay more-or-less in hand, shooting began again in the spring of 1977. The first scenes shot were many of the most complex and elaborate, and the site chosen was Pinewood Studios in England—the TV and film production studios known Fahrenheit 451, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Fiddler on the Roof, and more than a dozen James Bond thrillers. At the time, Pinewood was also flush from its success with a popular sci-fi TV series, Space: 1999.

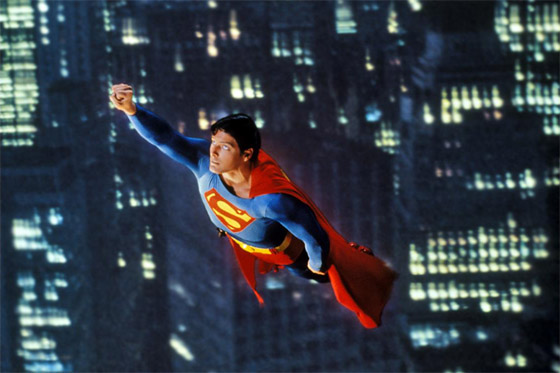

At Pinewood, the scenes with the most visual complexity were developed and filmed, including the sequences which take place on Krypton, home planet to Jor-El and Kal-El (Superman), as well as the millions of inhabitants of the doomed planet. Also shot at Pinewood: all scenes and segments at the North Pole and inside the Fortress of Solitude, Superman’s hideaway, and his place of learning and redemption. Finally, the now famous flying sequences—which in 1978 were considered marvels of cinematic technology—were also developed, tested and shot at Pinewood. Other large sections of the movie were filmed in the United States and Canada, notably New York City—which served as a logical cinematic stand-in for Metropolis—and Alberta, Canada, where it proved to be cheaper to recreate the quasi mythical American Midwest of Clark Kent’s youth and school education before his journey to the city.

Filming of Superman: The Movie ran into a long series of predictable and unpredictable problems, including scores of delays due to technical problems, mechanical failures, and the execution of stunts and special effects. In an age before widespread computer use in film production and in the pre-digital age, Donner and his special effects crew had to develop and improvise scores of techniques to achieve the believability of many of the stunts—notably the flying scenes. After dozens of failed attempts at using dummies and mannequins in some of the more dangerous scenes, and after a long series of attempts to develop animated versions and animated overlays of Superman in flight, producers and director agreed that the use of wires and blue screen would be the right course to follow.

The visual believability of the flying sequences became central to the overall effectiveness of the movie, the script for which already contained a wide range of large-scale special effects. Failure to make the fying sequences work for fans would likely destroy the movie's success. And though stunt men were used for some scenes, Reeve—working alongside rigging crews, effects coordinators and director Donner—performed many of the flying sequences himself. For scenes shot both in indoor studio venues as well as outdoors, Reeve would be harnessed inside a vest which would in turn be attached to thin wires. In the studio, the wires would lead to a series of dollies or tracks attached to the studio ceiling. Outdoors, the wires would be held aloft using cranes. Since the wires were very thin, many scenes give no hint of some form of filament holding Superman aloft. In shots where the wires were visible, they were removed in post-production using rotoscope methods—in essence the then-high-tech process of painting out unnecessary clutter on glass or some other transparent surface, or, the reverse, painting the primary figure and then projecting it over some other background. Though the technique had been around for decades on the film industry, Donner and his crew worked meticulously to raise the bar even higher for Superman’s flying sequences.

Still, that left lots of flying sequences—many of them unacceptable for shooting in the large studio or outdoors—left to complete. For this, Reeve was suspended in front of either blue screens or green screens (some of them developed specially for the Superman film project by 3M), and using specialized wind devices calibrated to create a sense of motion in his flowing or fluttering cape, the camera would be tracked manually or moved optically to enhance the sense of motion and vertigo. Then, in post-production, the footage of Reeve—in his Superman costume—would be placed in front of or behind whatever images were required, much of that footage obtained through helicopter or small aircraft. This combination of rear projection and front projection, coupled with meticulous work in the post-production phase, made the vast majority of Superman’s flying scenes—including those in which he flies carrying Lois Lane with him—highly effective. Only a few scenes seem to reveal themselves to be patently studio blue screen images, and the majority of those were scenes shot using rear projection.

In addition to the many flying sequences, Superman required special effects on a massive scale meant to rival—and if possible exceed—the big scale effects frequently used in popular “disaster” movies throughout the 1970s. Example: for a scene in which Superman attempts to thwart a huge California earthquake triggered by a nuclear missile launched by villain Lex Luthor, a 70-foot scale model of the Golden Gate Bridge was constructed. For the same earthquake sequence, a massive outdoor model of the Hoover dam was also created—some fifty feet wide and more than 40-feet in height. Scenes early in the film in which a helicopter spins out of control used both large models, as well as the real thing—a full-sized news helicopter on a rooftop. Entire sets were built to stage many scenes of recurring action: the Daily Planet newsroom and offices, Lois Lane’s apartment, Lex Luthor’s spacious underground lair under downtown Metropolis, the Fortress of Solitude, and the home and farmhouse used for Clark Kent’s early life.

The scene in which the young Clark Kent runs alongside a speeding passenger train was accomplished using a relatively low tech process: the passenger train moved along the train tracks at human running speed while actor Jeff East (East played the teenage version of Clark Kent in Smallville) ran along the parallel road; then, in post-production, the whole process was speeded up to make it appear that the young Clark Kent had the ability to outrun a speeding train. Still, the scene required enormous exertion on the part of East, who pulled a hamstring and sustained other minor injuries achieving the stunt.

Aside from the movie’s substantial technical achievements and its place in the history of special effects—it was released after Star Wars, its principal filming began before Close Encounters of the Third Kind, placing it critically and cinematically within the trio of major movies believed by film historians to have rebooted science fiction on the big screen—Superman’s dynamic, epic, three-chapter narrative helps sustain a movie both long in screen time (2 hours 20 minutes) and grand in scale and scope. Superman is effectively four small movies folded into one story: the birth of Kal-El and the story of his parents, especially his father Jor-El, on the planet Krypton, followed by the space journey which takes little Kal-El to Earth; the life of the young Clark Kent and that of his adoptive parents in the idyllic Smallville, complete with its mythic Americana visual and themes, and including the moral lessons as young Clark progresses into adulthood, culminating with the death of his father, which triggers another journey; next, Clark Kent’s discovery of who is really is within his Fortress of Solitude near the North Pole, listening to his father’s lectures and philosophical lessons; then, the story of Clark Kent/Superman in the big city, where he must quickly adapt to the ways of Metropolis and confront the criminal deeds of many, not the least of which is his newfound rival, the megalomaniac Lex Luthor. In today’s Hollywood, such a grand tale would told in distinctly separate packaged chapters, meaning multiple movies (as was the case with the Christopher Nolan-directed Batman series begun in 2005). Each of the four chapters is hinged upon a journey both physical and spiritual.

In a twist of fate, composer Jerry Goldsmith—who had reviewed the earlier Puzo versions of the script—was offered the job of scoring the movie, but because of his schedule and other commitments, was forced to walk away from the project. In his place John Williams was hired instead, whereupon Williams set about making the best of the film’s unusual blend of serious and not-so-serious themes and situations. Williams also relished the challenge found in the four-part epic narrative, meaning he would have to create four distinct musical tones and moods—one of Krypton, one for Smallville, one for the Arctic, and one for Metropolis. Williams also created musical themes for most of the major characters, some of the most memorable being those developed for Otis and Lois.

Some film buffs have noted that Superman: The Movie shares a striking overall thematic resemblance to the New Testament, including the frequent life-stage journeys, and the requirement—as imparted to him by his father—that Kal-El live among the humans as one of them, despite his obvious unlimited super powers. Parallels between The Bible and the Superman plot are numerous: General Zod is forever cast out of Krypton, just as Lucifer is cast out of Heaven; little Kal-El’s spaceship enters Earth’s atmosphere resembling not a meteor—as would be more scientifically likely—but as a small but bright star. The teenage-young adult Clark Kent must journey into the wilderness to find his purpose and his direction, emerging as a grown man with his powers and his message now intact. (Among the pre-recorded message his father, Jor-El, has left for the maturing Kal-El: live as one of them, Kal-El, to discover where your strengths and powers are needed. They [Earthlings] can be a great people, and they wish to be. They only lack the light to show them the way. For this reason, I have sent them you, my only son.)

Though screenwriters, producers and director have repeatedly said that no such parallel was intended, the seemingly constant thread of Judeo-Christian themes throughout Superman (and in all subsequent sequels with Reeve in the lead part) may have helped propel the film and its narrative forward with mainstream audiences—effectively channeling the movie from what could have easily been comic-book-nerd obscurity into the center of moviemaking success. (It has always been a central thematic article of faith that many comic book super heroes have a dark side, in some cases, very dark; thus the paradox: how make bright shining mainstream movie success out of sometimes dark matter ).

Nevertheless, Reeve—working with Donner and the carefully retooled screenplay—makes the part not only his own, but, according to many film historians, forever reboots his dueling characters of Clark Kent and Superman. As has often been pointed out, most super heroes have their real lives (Tony Stark, for example, or Bruce Wayne, or Bruce Banner), and their powerful after-hours alter egos (Iron Man, Batman, The Hulk, respectively). But Kal-El is now Superman, meaning that it is his Clark Kent character which is the fiction, the day-to-day charade. In this sense, Superman represents one of those rarest of superheroes whose power comes not from suits, gadgets, gimmicks or insect bites; Superman is Superman all day and all night, every day of the year; he must, however, maintain his "disguise" as Clark Kent, a bumbling, stumbling reporter for The Daily Planet.

Reeve captured the essence of this paradox perfectly, shifting neatly and comfortably—and with just the precise mix of humor and humility—between his Man of Steel character some to help enforce “truth, justice and the American way,” and his geeky Clark Kent, the small town-born metro writer whose jacket gets caught in elevator doors and who sometimes stumbles through his social interactions.

Adding to Reeve’s spot-on performance is the film’s skillful melding of a variety of American precepts and mythologies, and its grafting of post-war Baby Boomer cultural references and images. Though the comic book Superman had been introduced in the 1930s, Donner’s movie version arrives on Earth as an infant-toddler in the arms of the Kent family in the late 1940s, and his coming of age in the 1950s and early 1960s gave the contemporary late-1970s and early 80s audiences much well-blended nostalgia, atmospheric eye candy, and pop culture imagery to applaud.

And despite his high price, Brando proved well worth the paycheck, performing exceedingly well in his brief series of scenes at the film’s Krypton beginnings and in those scenes in which he instructs the young adult Kal-El. Gene Hackman and Ned Beatty often steal entire sequences for themselves as the mastermind villainous Lex Luthor and sidekick Otis respectively.

Though filming, especially the stunts and the special effects, were complex and took months longer than originally budgeted, the editing moved quickly. Principal shooting was completed in early October of 1978, including numerous reshoots to correct some problems. Still, editing was fast-tracked so that film could be released as a holiday package complete with many more millions spent on promotion and advertising.

Amidst much concern and trepidation on the part of executives at Warner Brothers—some of whom worried openly that the movie’s $58 million budget could sink the company—Superman: The Movie opened on December 10, 1978 (six months later than originally planned), premiering in a handful of theaters in Los Angeles, New York and Washington, D.C, then, four days later, in London. Over the next few days and weeks, it was released in more theaters across the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, gaining steam rapidly with audiences and generating mostly positive reactions from fans and reviewers.

Indeed, within the next three weeks, and prior to December 31, 1978, Superman had become the second biggest money-maker at the box office for the entire year of ’78 (the summer musical hit Grease beat it out by ten percent), and by the end of January Superman’s box office receipts had exceeded four times the film’s total cost, including all that pricey marketing and advertising.

Still, marketing can only carry an expensive motion picture so far. Had fans been disappointed or underwhelmed by Superman, the movie would have surely shown signs of suffering very quickly—a turn of events that may have spelled certain doom for Warner Brothers and the original investors in the comic book project. But fans were hardly disappointed. In fact, by late January of 1979, seven weeks after its opening, Superman: The Movie had become the sixth biggest box office money-maker of all time (Star Wars was safely ensconced in the number one spot).

Critics were almost as enthusiastic as the fans, many of the contemporary reviewers commenting on how well newcomer Reeve filled the screen and how easily he slipped into the role of the Man of Steel. Reeve also held his own amongst a cast swollen with A-List and B-List names, maintaining his screen presence in scenes with Gene Hackman, Margot Kidder, Jackie Cooper, Valerie Perrine, and dozens of others (he shared no actual screen time with Brando). Reeve so won over fans and critics that he instantly established his star-power despite the risk of being overshadowed at every turn. Film critics were especially impressed at Reeve’s apparent comfort with the story’s essential duality: a super hero whose natural condition in one of great physical power and whose mission is to help steer humankind toward a better place, but someone who must disguise himself in everyday life as an average Joe, in his case as the affable, agreeable, but bumbling Clark Kent. Superman established Reeve’s bona fides as an actor, and also brought him immediate A-List status.

The movie is not without its blemishes and defects. Some noted the film’s unevenness, most notably when the narrative and stylistic gears must suddenly shift to accommodate different characters—Gene Hackman’s often over-the-top comic interpretation of villain Luthor, along with that of his henchman Otis and his girlfriend Miss Tessmacher. The Luthor cadre’s campy, vaudevillian tone, which includes much overt slapstick, seems at times drawn as if from a different script than that of the complex, at times emotional middle American backstory which precedes Clark Kent’s arrival in Metropolis. Likewise, the romantic interludes between Superman and Lois Lane—in particular the “flying” sequences in which we hear Lois’s inner monologue—seem scripted for yet another movie altogether, what TR writer Maggie Nichols once called the “chick flick” factor, a mini-Lois-perspective subchapter grafted awkwardly upon the larger epic (why do we hear her private thoughts but not those of Clark Kent, or anyone else for that matter?)

Despite these flaws, or perhaps precisely because of their sometimes grinding gear changes, the movie remains dynamic—typically saving itself from implosion during these shifts by nevertheless keeping the audience enthralled and entertained. Thus the film’s chief weakness actually serves to showcase its chief strength—the ability to recover quickly and save the day, much like our hero. Whether this cinematic paradox was intentional on the part of Donner and the editors, who surely worked right up to the days and hours before the film’s Washington debut, remains unclear. What was clear to mainstream audiences at the time was that such tonal glitches mattered little in the end; the grand scale and rollicking good fun of the film, combined with the immediate likeability of Reeve, converted the movie from potential stink-bomb to instant classic, and elevated the film into the Pantheon of all-time box office hits.

Its more significant legacy then becomes even larger: the success of Superman not only paved the immediate and self-serving path for four sequels (all with Reeve in the lead role), but also cut a substantial path into the wilderness for all comic book and graphic novel screen adaptations to follow (including a score of Batman films stretched out over the decades), and more than 100 other movies based on the exploits of the hand-drawn characters and exceptionally-empowered heroes from our collective youths and past lives. And it stands the test of time: Superman: The Movie remains surprisingly fresh and enjoyable even now, four decades after it first appeared in theaters.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Spiderman Homecoming; Cameron Dale; Thursday Review; July 29, 2017.

Doctor Strange: Dazzling Visual Fun; Cameron Dale; Thursday Review; November 12, 2016.