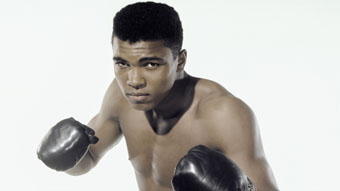

Stanley Weston/Getty Images/

www.history.com

Boxing Great Muhammad Ali Dies at

Age 74

| published June 4, 2016 |

By Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

Muhammad Ali, arguably the most famous boxer of the 20th century and the self-proclaimed “greatest of all time” in the ring, died early Saturday morning after a decades-long battle with Parkinson’s disease and a recent bout with respiratory failure. Earlier in the week, Ali had been hospitalized in Phoenix, Arizona after several days of problems with his breathing.

Ali was 74 years old. His family told reporters with NBC News and ABC News that a funeral and other services are being planned in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky.

Ali, who was born Cassius Clay, fought with Parkinson’s disease since his first diagnosis 32 years ago. The disease slowly depleted him of his physical power and agility, and also took away his famously nimble verbal skills.

In his prime, Ali had been a three-time world heavyweight boxing champion—a powerful puncher indeed, but for whom success in the ring often came as result of his unparalleled speed, agility and skill. Ali’s ability to best more powerful and stronger fighters was legendary, and it was his tactical genius inside the confines of the boxing ring which enabled him to compete with the other greats of his day, such as Joe Frazier and George Foreman.

Ali was born in Louisville in 1942 to middle class parents. A boxing prodigy, his success in the ring—a sport at which he became proficient at as early as age 12—brought him awards and accolades even as a teenager. By the time he was 18 he had already won numerous titles and Golden Gloves, and in 1960 joined the U.S. team at the Olympics in Rome, where he won a gold medal. Entering boxing as a professional the next year, Ali amassed a remarkable 19-0 record, rising quickly to the top of his sport. Only three years after his Olympic moment, Ali stunned the world with his defeat of Sonny Liston.

Ali went into the fight a 7-1 underdog, as most boxing analysts calculated that the fierce and formidable Liston, who had only a few years earlier knocked out Floyd Patterson, would make short work of a fight with Ali (then still calling himself Clay). It was in the run-up to that fight when Ali began to perfect his infamous manner of verbal banter—taunting opponents and sometimes openly ridiculing them. Ali deliberately spent days mocking Liston, and the verbal assault continued unabated right into the ring. The fight, which took place in Miami, became a game-changer for boxing. Ali won on points, but Liston was unable to continue to fight after having sustained a deep gash under one eye and serious pain in his shoulders. Liston could not—or would not—return in the seventh round. The fight was first time anyone in the ring had injured Liston.

Ali and Liston would meet again for a rematch, a controversial bout which lasted only a few minutes but burnished Ali’s title, and in essence made him the undisputed champ—a title he would retain off and on for more than a decade.

Ali would defend his title many times, and challenge others who took it from him. His March 1971 fight with Joe Frazier at Madison Square garden in New York is generally regarded by sports historians and boxing fans as the greatest heavyweight fight of all time—an intense, brutal struggle between the two best fighters of the period. Closely matched in strength, power and speed, the two fought a full 15 rounds before Frazier was declared the winner on points. The fight was so brutal that each man would leave the ring with serious injuries. Referee Arthur Mercante later recalled that the two fighters were hitting each other with unimaginable force, harder than any punches he had ever witnessed. In the final round, Frazier landed a powerful left punch to Ali’s face which dropped Ali to the canvass for several seconds. Mercante described the impact, which he saw from only three feet away, as “as hard as a man can be hit.” It would be Ali’s first professional loss in his career.

Ali would defeat Frazier in a later fight, but only after Ali lost to Ken Norton in 1973, and after Frazier was knocked down by George Foreman that same year. In Ali’s rematch with Frazier, the former had trained carefully to avoid Frazier’s dangerous left hooks.

By then, a match between Foreman—heavyweight champ by way of his devastating knockouts of both Frazier and Norton—and Ali, was inevitable. Ali was still considered the most skilled boxer tactically, but Foreman was generally rated as the hardest, most powerful puncher ever to have entered the ring. After many weeks of delays and much press excitement, Foreman and Ali met in Kinshasa, Zaire on October 30, 1974 in what promoter Don King had dubbed “the Rumble in the Jungle.” Foreman was no easy mark for Ali’s out-of-the-ring taunting and banter, for in his early boxing career, Foreman maintained an implacable, stony silence and exuded a fearful, intimidating composure. Ali’s previous injuries—along with his age—meant that he would face tall odds in defeating Foreman, who had already proved his lethal power by beating both Frazier and Norton.

Ali’s strategy, forged in secret, turned out to be an example of mental skill trumping power and strength. Ali fought what appeared to be a normal, by the book first round, then—in the second round—backed himself into the corner or against the ropes, where he carefully shielded himself from Foreman’s heavy blows. Ali guarded his face, and attempted wherever possible to protect his ribs, all the while taunting Foreman verbally. Increasingly angry at the defensive, seemingly cowardly tactics, Foreman hit Ali harder and harder, his punches largely ineffective as Ali crouched or coiled against the ropes. The result was predictable: Foreman began to tire, giving Ali the opening he sought. In the eighth round, calculating that Foreman had run out of gas, Ali let loose with a ferocious assault on Foreman’s face and head. As Foreman staggered about in the ring, Ali pounded Foreman until the stronger fighter simply collapsed from exhaustion and the full weight of Ali’s well-placed punches.

The fight was generally regarded as the biggest upset in boxing since James Braddock’s surprise win over Max Baer in 1935.

Ali and Frazier—the old bitter antagonists—would meet a third time in the Philippines, in 1975, in what promoters billed as the “Thriller in Manila.” Ali would win that fight, but only after a difficult struggle to maintain his strength and stamina against Frazier. Frazier’s trainer would refuse to let Frazier reenter the ring for the last round after cuts under both eyes had left Frazier’s face swollen and bleeding, and after it became unclear that Frazier could even see clearly. Both fighters were tired, and both had been depleted by the extreme tropical heat and humidity.

Ali’s life was full of controversy and media attention. Ali first came in contact with the Nation of Islam in 1959, but became a full-fledged member by 1962. He soon became friends with Malcolm X, and it was at this point that the young Cassius Clay decided to officially change his name to Muhammad Ali. Ali became the most prominent celebrity member of the Nation of Islam (often referred to in the mainstream press in those days as Black Muslims). His friendship with Malcolm was strained deeply, however, during the philosophical rift that developed between NOI leader Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X, a break which would lead to Malcolm’s excommunication from the larger organization. Ali chose to turn his back on his old friend Malcolm, a decision which he later said he regretted.

Many journalists initially refused to go along with Clay’s choice to rename himself Ali. One exception was Howard Cosell, senior sports commentator and analyst for ABC Sports. Cosell and Ali would eventually become close friends.

Ali famously refused induction into the military in April 1967. Ali said he had no quarrel with the people of Southeast Asia. He most controversially told reporters once that his refusal to fight in Vietnam was more basic than even his religious beliefs, in which the Quran teaches against violence. “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong; no Viet Cong ever called me nigger.” After his refusal to be inducted into the army, Ali was arrested under the provisions of the U.S. military code and civilian laws at the time. As a result of the felony, his license to fight was rescinded by the boxing authorities in New York—first the New York Boxing Commission, and later, within days, several other boxing and athletic organizations.

His refusal to fight in Vietnam led to a long court battle which worked its way through the courts for several years, eventually landing with the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971. In a famous decision, the court ruled 8-0 in favor of Ali, saying that it could find no distinction between Ali’s contention of conscientious objector and similar religious assertions by other American religious groups. The decision was viewed by some progressives and anti-war liberals as a quasi-repudiation of the war itself, though most legal scholars agree that the justices attempted to forge a verdict based strictly on the facts surrounding Ali’s case.

During his exile from boxing, and while his case worked its way through the courts, Ali joined the anti-war movement, and began to work more closely with civil rights causes. He also launched a speaking tour of American college campuses, and supplemented his income through speaking engagements and media appearances.

Ali’s years of preeminence in boxing are generally regarded by sports historians as “The Golden Age of Boxing,” a period in which several of boxing’s most skilled and powerful fighters—among them Ali, Frazier, Foreman and Norton.

Related Thursday Review articles:

The Most Brutal Sport; Earl H. Perkins; Thursday Review; January 29, 2014.

Panthers Fail to Topple Dolphins’ Landmark Record; Keith H. Roberts; Thursday Review; December 28, 2015.