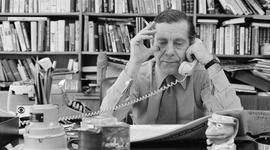

Photo courtesy of CBS News

Morley Safer, 60 Minutes Legend, Dead at 84

| published May 19, 2016 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

A legendary reporter has died—one who can trace his hard work back to the Vietnam War and to the earliest days of one of the most popular news shows ever created for television.

Veteran TV journalist Morley Safer, who was a fixture of the 60 Minutes reporting team for decades, died this week at age 84 only weeks after announcing his decision to retire. Officially, the cause of his death was pneumonia. Among his various awards and recognitions, he won a dozen Emmy’s, three prestigious Peabody Awards, and at least two Alfred I DuPont-Columbia University journalism awards for his work as a reporter.

Safer also won a lifetime achievement award from the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences in 2009, and two George Polk Memorial Awards for investigative journalism.

Safer gained his most notably early recognition with his firsthand reporting from the front lines in Vietnam. His August 1965 CBS News report from the war-ravaged village of Cam Ne is considered one of the most important news pieces to emerge from what was at the time a war still largely supported by the American public.

On August 3, 1965, Cam Ne was deliberately torched by U.S. Marines under instructions from both U.S. commanders and the local provincial political leaders. Safer and his South Vietnamese cameraman caught the entire episode on film, and the report was put together back in Da Nang late that night and transmitted via telex back to CBS in New York, where producer Fred Friendly sought hurriedly to verify the striking and powerful images. Safer, who had been invited to accompany the Marines on the mission, narrated some parts of the burning of the village in real time as the incident unfolded, starting with a single Marine using a steel cigarette lighter to set fire to a hut, followed by more houses and structures being set afire. Within moments, some of the Marines were using flamethrowers to destroy the village.

So concerned was Friendly about the potential for negative reaction to the news report that he asked for others to watch the film footage before it was aired. Walter Cronkite, CBS President Frank Stanton and other top brass sat in on a screening, and they too were immediately struck by the potential for negative blowback, but after a lengthy discussion agreed that Safer’s report merited being aired in unedited form.

The blowback was indeed swift and severe, and triggered immediate accusations in some quarters that CBS was deliberately airing highly critical reports about the war to stir up anti-war sentiments. The report also stoked the ire of President Lyndon Johnson, who personally called Stanton and others a CBS to lambast them for the negative report. Suspicious that Safer might be a communist or an agitator, Johnson ordered a full security and background check of Safer, which produced nothing unusual and no surprises. Safer was briefly banned by Major General Lewis Walt from access to any I Corps combat operations in Vietnam, though later he was able again to report normally but with some limitations.

After his stint as a reporter in Southeast Asia, Safer was sent to London to serve as bureau chief and senior editor, a position he would hold for about three years.

Safer would join the 60 Minutes team in the 1970s, a role he would retain for the remainder of his career. As a member of the popular newsmagazine’s regular team of journalists, Safer would report on politics, art, culture, education, technology and automobiles. Safer in particular loved art, a subject he reported on with some frequency.

Safer was born in Toronto, Canada to Jewish parents of Austrian and Russian descent. Safer says he decided as a teenager to become a journalist and a foreign correspondent after reading some of Ernest Hemingway’s early works. Though he studied writing and journalism in school, Safer dropped out of college before graduating, choosing instead—like many other young reporters—to go straight into newspaper work without completing formal education.

Safer wrote for several Canadian and British newspapers, and also provided copy for news services such as Reuters, before going to work for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1955. Among his first experiences with foreign reporting and war coverage: the 1956 Suez Crisis in Egypt, a brief but deadly war which broke out between Israel and Egypt.

Safer may have also singlehandedly saved 60 Minutes from eventual extinction. After struggling with poor and fair-to-middling ratings for several years, the newsmagazine show looked to be facing a the chopping block by the mid-1970s. Safer’s 1975 interview with First Lady Betty Ford—in which topics included sex, alcohol, abortion and drugs—brought about a healthy ratings spike and catapulted the show into the top ten, where it has stayed off and on for decades.

Safer may have earned the singular merit for having saved the wine industry in the United States, and altered forever the drinking habits of television viewers in the U.S. after his 1991 piece about the apparent health benefits of red wine in which he highlighted “the French Paradox,” that Europeans who drink modest amounts of red wine live longer despite diets otherwise not as healthy as their American counterparts.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Bob Simon, Rest in Peace; Thursday Review; Thursday Review; February 12, 2015.

Going the Distance: Steve Byrnes, Rest in Peace; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; April 26, 2016.