Images courtesy of Paramount Pictures/

Hughes Films

Save Ferris: 30 Years a Classic:

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

| published June 21, 2016 |

By Keith H. Roberts, Thursday Review

Let’s cut to the chase: Ferris Bueller’s Day Off may be the greatest comedy of the 1980s. Why? Because it spawned some of the most famous movie lines of all time, several of the funniest scenes ever produced, involved the total destruction of an expensive limited edition cherry red Ferrari, and it made Ben Stein immensely famous. Enough said.

Also, the movie is wildly original, and avoided all the highly recycled clichés and retreaded themes wrought by the vast majority of Brat Pack films of the era, including classics such as The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles (movies that put Mollie Ringwald and Anthony Michael Hall on the map), along with all the lesser youth oriented stuff of the period.

You can quickly date yourself if you remember first seeing Ferris Bueller's Day Off--which starred Matthew Broderick, Mia Sara, Alan Ruck, and Jennifer Grey—at the theater, or shortly thereafter on cable television, where it remained a staple for years. In fact, the movie’s prime has neither peaked nor faded, and it remains fresh and funny even now, decades later—easily the definition of a classic by most critics measurements.

The plot is cunningly simple: a wisecracking but highly popular high school senior, played by Matthew Broderick, decides to skip school one fine spring day in suburban Chicago. He feigns a headache and upset stomach, fooling his parents but not his meddlesome, busybody sister. Minutes after his mom and dad exit the house for their jobs, young Ferris begins his day of carefully planned leisure and fair weather mayhem, drawing into his elaborate truancy conspiracy as his companions two of his closest friends—girlfriend Sloane (played by Mia Sara) and best buddy Cameron (played by Alan Ruck).

There are risks, of course, not the least of which is the wrath of the comically overbearing Dean of Students, who rightfully distrusts Bueller’s claim of illness—the student’s ninth absence of the school year. Played to perfection by actor Jeffrey Jones, the subplot of the suspicious Dean Ed Rooney becomes one of two parallel stories—including that of Ferris’s equally distrustful sister (Jennifer Grey); both seek to dislodge Ferris from his day of leisure by exposing him as a serial class-cutter, a fraud, and a chronic hedonist.

The two subplots operate alongside that of Ferris’s extensive outing, which includes a combination of vacation-like sight-seeing and mind-expanding field trips: art museums, the commodities exchange, the observation level of the Sears Tower, a Cubs baseball game, a nauseatingly frou-frou French restaurant, a German-American Day parade through downtown.

Cocky and self-confident, the young Bueller is certain that he can have his cake and eat it too—a full day of fair weather fun, while successfully avoiding the very real consequences of skipping classes and possibly risking not merely his GPA, but also his projected graduation date. Perceiving himself as a sort of student version of James Bond (he compares himself to Bond early in the film), he is confident that he and his sidekicks can dance between the raindrops of school suspension and parental grounding.

So far so good. But what makes the film perhaps even funnier and more original are the on-target depictions of typical suburban high school life, with Bueller at the center of the complex social system of preppies, geeks, greasers, nerds, jocks and band dorks that make up the tapestry of activity and school social order: even as he avoids school that day, a cadre of supportive students—some thinking he really is sick, others in on the joke—seem part of his gravitational pull.

Rooney, meanwhile, imagines himself somehow in control of the halls and the closed classrooms and the minions of Bueller, roaming the halls in search of clues, then, finally launching his own one-man detective campaign to find the truant Ferris and bring him to a long-overdue justice. He believes it is his duty to expose Bueller as a charlatan and an incorrigibly bad example, before the antics of one student propel scores of others down the path to certain destruction.

Of course, the audience is meant to root for the young Ferris, who narrowly escapes exposure several times. Though he is comically endearing and very nearly steals the scenes with his deadpan seriousness and earnestness, Rooney—as the Dean of Students—is nevertheless the guy we are not rooting for; indeed, as each pratfall becomes more violent and more destructive, we correctly find ourselves cheering for his eventual total humiliation and comeuppance, and revel in the deconstructive power of his deepening predicaments. In the end, he is bested not merely by the unstoppable Bueller, but by his own delusions of control over a community of kids and teens.

Written and directed by John Hughes, at a time when Hughes was at top of his game in this genre, the film remains hilarious with its quirky combination of slapstick gags and deadpan humor. It also seems remarkably fresh and relevant despite some 30 years having passed since its original release: it never occurs to us to ask about the utter lack of cell phones or smart phones, nor do we flinch at the sight of those ancient IBMs and Apple IIs. Tak Fujimoto’s impeccable cinematography and Paul Hirsch’s dead-on editing add to the movie’s quality, and also help to burnish the film’s staying power as one of the classics of the era.

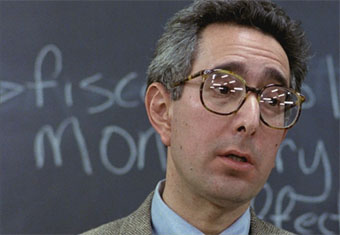

Plus, there is the added and almost priceless benefit for posterity: the film introduced a little known economist, thinker and writer by the name of Ben Stein to the public at large. His scant few cameos—as, appropriately, a droll, deadpan, teacher of economics—are among some of the funniest in movie history, and his most quotable lines (“Bueller….Bueller….Bueller…”) remain so iconic that even now Stein admits he cannot wander into public without people of all ages throwing the lines back at him (“something d-o-o economics…voodoo economics”). Stein barely had to act for those tiny scenes, and some can make the reasonable argument that his cameo in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off so altered the trajectory of his career that he should give a lifetime of credit to both writer-director Hughes, and to actor Broderick—for whom he shares no screen time.

Toward the end of the film, Ferris’s overreach nearly causes his world to collapse: he has over-extended his day of leisure and high-impact fun and may be minutes away from being caught, with all the usual extended punishments which await a high school kid who has unwisely attempted to juggle too many balls at the same time. But, he survives—lucky that he has parents who are apparently inept and near-sighted, and imbued by the Gods of Truancy with a nemesis (Dean Rooney) who proves comically unable to control his most troublesome student adversary.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) bears inescapable comparison to a film with a similar set of circumstances, Risky Business (1983), which starred a very young Tom Cruise and a sexy Rebecca De Mornay.

In Risky Business (written and directed by Paul Brickman), the young Joel (Cruise) seeks to relieve his suburban boredom, not through skipping class specifically, but through his hiring an expensive prostitute for a night of carnal fun while his parents are away on vacation/business trip. Joel’s adventure, predictably, turns darker, more dangerous, and certainly more costly (both movies features catastrophically damaged high-end sports cars!) than Ferris’s simple day of baseball, parades, and springtime Midwestern sunshine.

Both films take place in the mostly white, largely upper middle class leafy suburbs of Chicago. And both involve students on the verge of adulthood, now weighing—perhaps for the first time—the very real consequences of their actions, risks versus rewards; a deep enough infraction could make the difference between a fine college education at a high-end school, versus the state university. Both films stand the test of time quite well, with poignant observations about teenage life mixed with coming-of-age challenges. (Throwback Thursday: TR writer Randy Pooler reviewed Risky Business in the print edition of our June 1983 issue, giving it a decidedly upbeat thumbs-up).

But where Risky Business dwells deeply into the dark side of youthful misadventure—Joel’s night of bliss with his prostitute-turned-friend turns complex and dangerous, drawing in the ire of a low level gangster and enticing a legion of his friends to engage other similarly connected hookers—Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is all about good clean fun. Hughes’ classic refuses to take itself seriously as social commentary; Broderick frequently “breaks the plane,” looking directly at the viewer, occasionally engaging in commentary with the audience, happily encouraging deconstruction of the film’s meaning, and even imploring the audience to “go home” in a brief post-credit-scrolling scene.

Ferris Bueller's Day Off cost a mere $6 million to produce—small budget even for the mid-80s teen classics—but it would eventually rake in about $72.5 in box office gross. It would also go on to become such a staple of HBO, Showtime, Blockbuster VHS and DVD that it would earn almost as much in redistribution monies over time. Even now, it remains a popular movie haunting a variety of movie channels. Though, if you have never seen it in its totality, I strongly suggest you watch it the first time on DVD or Blu-ray, uninterrupted and with the added benefit of no one around to hear your belly laughs and screams, unless you have teens in your family, in which case they will thank you for opening their eyes to a classic comedy.

Three decades later, Ferris Bueller's Day Off remains as funny as it was when it was released in late May of 1986.

Related Thursday Review articles:

When Time Travel Was Fun:Back to the Future at 30; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; September 12, 2015

Six Movies That Made Me Pee in My Pants Laughing; Keith H. Roberts;Thursday Review; August 13, 2015.