Striving Against Darkness:

The Story of Holocaust Survivor Ann Rosenheck

| published November 7, 2015 |

By Jennifer Walker-James,

Thursday Review features writer

In the Old Testament, it is said that the soul of man is the candle of God. Thus, the flickering of the candle’s tiny flame serves as a reminder of life’s precious fragility. And just as the flame itself must breath, change, grow, and strive against the darkness before ultimately fading, so must the human soul.

No greater darkness has shadowed the earth quite like that of the evil that was the Holocaust, but no light has shattered the darkness than that of those who endured its monstrosity. 1933 marked the beginning of the end for the majority of Europe’s Jewish population. By 1939, Jews were plucked from their homes and forced into Jewish ghettos where they waited for their fate to be determined by governing officials of the Third Reich.

Imagine waking to the sinister cadence of Nazi footsteps marching outside your window—the clamor of Death itself knocking at your door. Picture a world where in one day, you are stripped of everything from the hair on your head to the shoes on your feet—a world where you now have a number instead of a name. It is a place where reality seems to have forgotten to lock away nightmares. It is a place so cold, winter’s icy breathe stirs a growing numbness that spreads from the tips of your bare feet to the depths of your heart. Hunger is now the only thing your body feels. Hunger, or pain. And freedom only exists as a faded memory…along with the rest of your family.

Such was the case for the millions forced to suffer the demonic plague that was the Holocaust. Those who were fortunate enough to survive and escape its surly grasp did not do so without being forever scarred by the darkness. And it is with the retelling of these unbelievable horrors that survivors like Ann Rosenheck offer the world a renewed light of inspiration and hope.

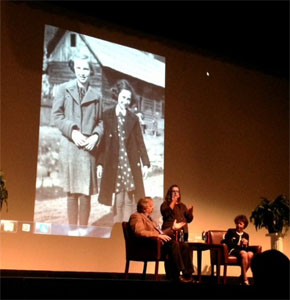

Thursday Review was privileged to get to meet Ann as she recalled the terrors she survived at Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps with a packed audience at Troy University’s main campus Thursday. Her story is many things; it’s a tale of courage in the face of evil’s darkest form, escape, healing, and ultimately, forgiveness.

Ann Rosenheck was born in Rachov, Czechoslovakia. In 1939, when she was only 13 years old, she and her family were among the first in their town who were sent to live in the Jewish ghetto. Given only ten minutes to pack her belongings, Ann chose to take only her most precious belongings—her books. Among her favorites in tow was a copy of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. The Rosenheck family was among 38 selected to go on the first passenger train. Upon arrival, they were forced to stay in a cemetery that was a makeshift holding camp in the frosty depths of Hungary.

“There was no shelter—no tents. We had nothing to hold onto except each other,” she recalls.

After a few days, they were moved into a home where they lived in the stable. Six weeks later, just as they were among the first to be sent to the ghetto, they were also the first sent to wait at the railroad tracks in Rachov. When they got there, Ann’s older sister who was married with two children of her own met them there. Her father asked his oldest daughter what she was doing—she had not been chosen.

“My sister looked at him and she said, ‘Papa, whatever happens to you, is going to happen to me,’” Ann recalls. So along with her father, her mother, an uncle, her sister, and her two nephews (ages 4 and 6), Ann waited for their fate to arrive. When it did, it came in the form of a bustling entourage of cattle cars rattling to a halt in front of them.

“They wanted us to get in, but the car was this high off the ground,” Ann says, her outstretched hand signaling the railcar’s 5ft height. “And I had to jump in,” she adds, implying the daunting challenge for her petite frame. “And we had little time to get in. In front of us was the train and the Nazis were running behind us.” Ann goes on to describe the horrors of watching as people were shot or beaten and then trampled as people were herded into the cars like animals. Amid the bedlam of confusion and terror, Ann grabbed one of her nephews and climbed into the car along with her father and mother, leaving her sister and remaining nephew to be loaded onto a neighboring car.

Once inside the car, Ann’s father noticed a wooden plank resting on the barbed wires of the tiny windows on either wall. Quick ingenuity led him to hoist her and her nephew onto it so they’d have a place to sit. When the doors of the car roared shut, there were 109 people and only two buckets—one with water (that quickly became empty) and the other to be used for human excrement. As one could imagine, with so many people, the first bucket emptied while the latter was soon overflowing. Ann recalled sticking her fingertips through the tiny openings of the window to retrieve raindrops to quench her thirst.

Four days later, their trek ended at the doorsteps of Auschwitz. Once unloaded from the train, the men and women were separated into groups with rows of five. Ann recalled how when she first arrived to the ghetto, her mother and father told her to say she was seventeen. At first, she refused, citing she couldn’t tell a lie. Little did she know the bearing it would have on her fate. Reluctantly, she did as she was told and to aid in her disguise, she wore a babushka.

Under the selection of the “Angel of Death Nazi” Josef Mengele, Ann and her family were sorted in the infamous Holocaust selection process. Lying about her age was ever more crucial for her survival as children fourteen and under were immediately asked to step to the left, along with the elderly or anyone else deemed unfit for work. Those directed to step links were boarded onto the trucks waiting to carry them to the crematoriums. Ann’s father and uncle were among this first wave of executions.

“Papa looked at me and, calling me by my nickname, he said ‘Ansika, you must take care of your mother and sister now.’ While the SS were forcing us toward the camp, I turned and watched as they loaded my uncle and my father into a truck.” Ann pauses, choking back her emotion. “I never told my mother what I saw, but I saw them taken to the crematorium.”

Once taken to the blocks where they were to be housed, another selection process separated Ann from her mother and sister. She never saw them again. Older women and mothers with small children had the smallest of chances of avoiding the gas chambers.

“It was March, but it was still cold in Germany. And they forced us into these crowded barracks where we were stacked on top of one another. And I was forced into this bunk with this beautiful Yugoslavian girl,” Ann’s voice dims, starting to fade. “It was very, very cold. And I was a young girl and all I knew was the Yugoslavian girl was very hot and we had no blankets so I stayed beside her all night. Then, the next morning someone looked at her and said, ‘Oh my God! She’s dead!’ I was a young girl and I didn’t know what death looked like. I told them she wasn’t dead because her eyes were still open. But she was. She died in the night.”

The next day, Ann was processed into the camp where they shaved her head and she was given the number 20381 that would be her identity the remainder of the Holocaust.

“They made us take off our clothes. At first, we didn’t want to, but they shot and beat anyone who didn’t so we had no choice.”

Ann and the rest of the women in her camp were given grey dresses to wear. Being only 13 and of a very petite frame, it’s no surprise that the one-size-fits-all garment was much too long for her—too much so for her to even walk. After being refused alterations from the SS officers or any staff members, other women at the camp ripped the front of her gown enough so that she could maneuver without tripping. During her tenure, she served as a housemaid for one of the SS officers. Her first “punishment” came after being caught stealing turnips from the storage barn—her hands were just small enough to fit between the slats of the crates they were in. She was beaten and forced to carry rocks, but starvation and frailty made those heavy loads impossible. So the SS instead gave her bricks to carry since they were easier to stack.

After four months at Auschwitz, Ann was taken to Dachau where, again, she worked in an ammunition factory. While there, she was yet again “punished” when it was discovered that she had allowed a girl who was ill bathe in the wash basins. Her offense sent her to the crematorium where her life was spared due to it having reached capacity just prior to her arrival. But that did not shield her from the ghastly images of what was taking place within its walls.

“They did ugliness on beautiful men. They castrated them…” Ann voice begins to quiver. “They took a beautiful woman and made her legs like a dog.”

Meanwhile, she was sent back through another “selection” process where her doomed fate quickly faded into that of hope when the Polish doctor examining her told one of the SS guards that she may have Typhoid fever—a ploy to get her sent to the infirmary where her salvation awaited in the most unlikely of forms.

While waiting in the room to be taken to an unknown destiny, a Nazi guard came in and divulged the most shocking of secrets to Ann—that he, too, was Jewish.

“He whispered, ‘They never found out that I was a Jew,’” Ann smiled. And it was through the officer’s and the Polish doctor’s clandestine efforts that she was taken to a group of Czech Christians who hid her until being liberated by American soldiers in April of 1945. “The first American I saw…” Tears build in her voice as she continues, “It was unbelievable…unreal.” When asked what she would like to eat, her response was simple. “I told them I simply wanted bread and butter.”

After three years of living at a displaced persons camp in Germany, Ann arrived in the U.S. in 1948. One year later, she reconnected with her childhood sweetheart, Ike and they were married. After thirty years of living in New York, Ike and Ann moved to Miami, Florida. One day, while waiting to get on an elevator at the complex where they lived, she said something to Ike in German and the couple next to them looked up. She recognized the woman, but could not put a name to the face. Soon, the couple introduced themselves to Ike and Ann and revealed that they were from Germany.

The next day, a bouquet of flowers was placed outside their doorstep, though they didn’t realize until later on who they were from.

Still puzzled by the inexplicable familiarity about the German woman, Ann continued to be wary while Ike and the woman’s husband became close friends. It wouldn’t be until later that Ann would learn that the woman was in fact an SS officer, but because Ann and Ike had developed such a close relationship to her husband, she chose to forgive.

When the Holocaust Memorial Miami Beach was opened in 1990, Ann joined as a speaker. Since then, she has continued to share her story across the U.S. In 2006, Ann visited Waynesboro Middle School in Virginia. In 2007, she returned to her hometown of Rachov in the present-day Ukraine for the first time since being carted off to the ghetto.

Currently, Ann is working with the Foundation for the Holocaust Education Projects to continue bringing Holocaust education and awareness to many communities across the U.S. To learn more about this ongoing endeavor, one can visit their website at holocausteducationprojects.org. After World War II ended and the remaining victims of the Holocaust were liberated, it was determined that over six million Jews died in concentration camps. At least 1.1 million of these victims were children. One in six Jews killed in the Holocaust died in the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

Anne Frank once wrote, “Look at how a single candle can both defy and define the darkness.” In a stark turn of events, both she and Ann Rosenheck would be set to face the greatest darkness to ever mark the earth at Auschwitz. But the unwavering candles that are the souls of Holocaust survivors like Ann Rosenheck continue to strive against the shadows, spilling light into the hearts of all who are privileged enough to hear their story.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Irena Sendler, Humanitarian; Earl Perkins; Thursday Review; January 23, 2014.

The Father of the Civil Rights Movement; Earl Perkins; Thursday Review; February 26, 2014.