2001: A Space Odyssey:

Fifty Years Ago Science Fiction Changed Our World

| published April 12, 2018 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

Some films are meant to be seen on the big screen. This may be a cliché, but as several of our Thursday Review writers have pointed out over the years (Michael Bush, Maggie Nichols, Cameron Dale, Katie Mineer, to name a few) it’s a cliché which still rings true once or twice each cinema season. Home TV screen size doesn’t matter, nor does your aversion to crowded multiplexes with high- priced tickets, expensive popcorn and $5 soft drinks: some movies are best enjoyed in a theater, power and grandeur intact. Often, it is the vision and skill of the director which can make the difference.

As a baby boomer I look back across my lifetime and only now appreciate some of the stuff my parents dragged me to see in theaters, often against my preference—The Sound of Music (my mother’s personal favorite from that era) and Patton (one of my dad’s top choices) to name two examples—as well as the films I went to see at the theater on my own or with friends; Mary Poppins, Planet of the Apes, Barry Lyndon, and American Graffiti all come easily to my memory. Only now, comfortably in my middle age, do I fully grasp the concept of the big screen experience—especially those in cavernous theaters with the enormous screens and the wide projection systems. The motion picture is—generally, and depending on director and cinematographer—an art form requiring a large canvas.

Then, as an adult, I decided I did like The Sound of Music and Patton, and I thank my conservative parents for insisting I participate in what—even at that tender age—I considered cornball movie experiences. And one of the things I am proud of to this day—in addition to bragging to Gen-X hipsters and Gen-Y tikes that I saw all the good rock concerts—is that I had the courage, determination (and $3.50 in hard-earned lawn care money) to see 2001: A Space Odyssey on the biggest of the big screens with a group of friends who appreciated both science and science fiction.

Indeed, if one were to objectively name only a dozen contemporary films that fall into the category of must-see on the large screen (a list that might also include Ben Hur, Star Wars, Gone With The Wind) Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey would certainly make the cut. Even if you do not have the opportunity to see these in a theater (in larger cities, there have been occasional retrospective releases of all four over the years), when you get around to making your next television screen upgrade in your home, you should make it a priority to rent or purchase 2001 on DVD or Blu-ray. (See our ancient article from 2012: "A Few Movies You Must Own on Blue Ray or DVD").

Better still, plan to catch it this spring in selected theaters upon its rerelease to celebrate the film’s 50th birthday. On May 18, director-writer-producer Christopher Nolan (Batman Begins; Inception; Dunkirk) will step onto the stage at the Cannes film festival and introduce an “unrestored, unaltered” 70 mm print version of 2001: A Space Odyssey to event attendees. Among those in the audience will be members of Kubrick’s family and some of the surviving film crew. The Cannes version has been meticulously reprinted but unaltered from the original negatives—meaning the experience will, in theory, very closely resemble what audiences saw upon the movie’s 1968 release. Later in 2018, Warner Brothers and MGM plan to re-release this classic on Blu-ray and DVD in a remastered 4K version, complete with all the tools of digital revamping. I can already predict that I may be among those whose choose to order this version as soon as it is available.

Normally in this kind of retrospective review, we would bore Thursday Review readers with a lot of background and context prior to the big takeaway.

But let’s not waste time, nor mince words: 2001: A Space Odyssey became the most influential sci-fi film of all time, a movie that recalibrated almost everything we thought we knew about science fiction on the big screen and literally rebooted the genre of sci-fi. So profound was the overall impact of its cinematic and scientific canons that hardly any sci-fi film since has escaped its influence in the 50 years after its release in 1968. 2001 directly shaped the visions of future director-writers George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott and others. Furthermore, it can be reasonably argued that the film even extended its power and influence into the hard sciences by reshaping science-fiction—often a driver of interest in space exploration in the modern era—and propelling our imaginations toward what is possible in the near and distant future (much in the way that the television series Star Trek channeled interest in space travel into a variety of now commonplace technological concepts and real-science outcomes).

Indeed, 2001’s wide legacy impacted nearly every other notable sci-fi movie since its original release, from the epic Star Wars and Star Trek film franchises, to Ridley Scott’s Alien to James Cameron’s Aliens, from Blade Runner to The Terminator, from Gravity to Interstellar to The Martian. Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece 2001 effectively set down certain basic rules about look, style, tone, and adherence to scientific principal which remain intact now, 50 years later. Kubrick set the bar so high and so firmly that no sci-fi movie since—even those crafted for comedic or ironic effect—have been able to escape the absolute gravity established by 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Then, setting aside the “science” part of the equation, 2001: A Space Odyssey became, quite simply, one of the most important films ever produced—in any nation or in any language.

One of the most notable aspects of 2001, and perhaps one of the keys to its success, was its remarkably effective fusion of the visions of two great 20th Century artisans—writer and science visionary Arthur C. Clarke, and film director Stanley Kubrick. This collaboration between writer and director would prove to be, arguably, one of the great distinctions of the film’s transformative power and its extensive legacy.

Clarke had a long-established reputation as an imaginative writer and futurist philosopher. The author of classic sci-fi novels such as Childhood’s End (1953) and Islands in the Sky (1952), Clarke was also an avid and relentless thinker and tinkerer with scientific ideas, prescient as far back as the late 1940s and early 1950s to accurately predict how certain forms of space travel and global communications might ultimately develop, among them his notion that geostationary satellites might one day become the touchstone of worldwide telecommunication, including radio, telephony, and television, then still in its infancy.

Likewise, Kubrick had already proven himself to be a director of astonishing skill and vision, a relentless perfectionist with a penchant for being far ahead of the curve, especially in social thinking. In 1957’s Paths of Glory, the director forged an eloquent anti-war statement which seemed a prescient template for the futility the United States would face in Vietnam. In 1964’s Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb, Kubrick offered moviegoers a darkly comedic interpretation of Cold War insanity, only months after the Cuban Missile Crisis and several years before Henry Kissinger—long-rumored to be the model for the character Strangelove—would come to popular prominence. Kubrick would go on to direct several masterpieces of the cinema after 2001, including Barry Lyndon (1976), The Shining (1980), and Full Metal Jacket (1987).

Based in part on Clarke’s novella The Sentinel, written several years earlier, the film 2001: A Space Odyssey was accompanied by a novel—written more-or-less as an adjunct to the movie script—which fleshes out the larger set of stories and circumstances depicted in the film; that novelized version was published around the same time that the film first premiered in 1968. But this oversimplifies the long run-up to the movie, a development process which took several years for both Kubrick and Clarke.

The individual successes of Paths of Glory and Dr. Strangelove had driven the restless filmmaker Kubrick to look toward other subjects and genres to explore on the big screen—in this case Kubrick’s long interest in science fiction and space travel. After some discussions along those lines with studio executives and potential film backers, a meeting was arranged between Clarke (who at the time lived in Sri Lanka) and Kubrick. The two met in New York City where, according to Clarke’s meticulous journal notes, they began kicking around ideas over lunch and drinks at Trader Vic’s. They would meet again and again over the next weeks and months, bouncing ideas off of each other and sharing material. Eventually, the two would merge the major elements of The Sentinel with another Clarke short story, Encounter in the Dawn, into one single narrative film treatment, tentatively entitled Journey Beyond the Stars—an epic, multipart motion picture concept which both filmmaker Kubrick and writer Clarke hoped might transform how people viewed space exploration through the prism of the cinema.

Their collaboration would consume much of their time throughout the next three years, just as the real world space race was reaching its zenith of speed and intensity, and just as the space programs of both the United States and the Soviet Union were each taking increasingly robust strides toward deep space exploration. Among the far-reaching themes Clarke and Kubrick sought to include within the film’s philosophical boundaries: the origins of mankind’s intelligence; the eventual routine nature of near-space travel (space stations, colonization of the moon), deep space exploration, alien lifeforms, computer technology and artificial intelligence, and one of Kubrick’s most persistent cinematic themes—existentialism and dehumanization.

Ultimately their screenplay would effectively draw viewers into these complex arenas as if by hypnosis—a major reason the film is often cited as one of the influential movies ever made, and not just within the genre of sci-fi. It is also why the film is often regarded as a monument to the grandeur wrought by the non-narrative, non-verbal, less-is-more style often associated with a few of Kubrick’s notably minimalist works (The Shining; Eyes Wide Shut). Written concurrently but separately, Clarke’s novelized version and Kubrick’s screenplay diverged somewhat during development, even as each routinely checked with the other to ensure sufficient collaborative strength. Clarke’s novel, also regarded as a classic (but nevertheless overshadowed by the film at the time and over the subsequent decades), was far more explanatory and expository than Kubrick’s screenplay, which relied far more on non-verbal cues and symbolism.

In the end, both creative spirits ultimately found sufficient convergence and overlap in the final drafts of the screen version to proceed. After a few last moment changes which may have greatly skewed the film’s power and mystery, Kubrick and Clarke were in more-or-less broad agreement in the movie’s general storyline. (Example: in the original version, Earth-orbit satellites seen briefly early in the movie were to be revealed to be nuclear weapons platforms, detonated by the “Star Child” creature at the end of the film; Kubrick jettisoned this since it would too closely resemble the final frames of Dr. Strangelove)

The film’s plot breaks along sharp chapter lines, seemingly unrelated save for one constant—and, as it will turn out, pivotal appearance by an alien artifact or device.

Chapter One examines a small tribe of pre-human, ape-like creatures at the “dawn of man” somewhere in central Africa. The tribe has leaders, children, and has tentative possession of its own home-base watering hole. But soon the tribe is challenged by a somewhat more aggressive group of similar proto-humans, who—using noise and violent gesture—effectively drive the first tribe from its home. Days later, those driven from their watering hole awaken in the morning light to discover a shiny black rectangular object in the dry soil near where they have slept. Terrified but intensely curious, the apes encircle the object—a tall, smooth black monolith—shrieking and cowering, while also moving ever closer, touching and stroking the object. Later, perhaps influenced directly by intellectual intervention by the alien monolith, one of the apes discovers that he can use the large, sun-bleached thigh bone of a dead creature as a tool with which to strike an object. Hammering at small bones and skulls, he and his fellow tribe-creatures quickly reason that the large bone could be used also as a weapon. The next day, they challenge the interlopers at their old watering hole. Striking the leading rival ape with the thigh bone, rendering him injured and unconscious, the first tribe effectively chases the second tribe from the watering hole, leaving us to conclude that the first use of tools by pre-humans may have also simultaneously been the first use of a weapon of war. We are left with the question only of what purpose did the alien device have when it seemingly intervened in the struggle.

In a cathartic moment at the end of the chapter, an ape exuberantly tosses his newly discovered tool-weapon into the air as the camera tilts upward to follow its slow arc.

Then, in what may be the most famous jump-cut (in this case a “match-cut”) in all of cinema, the scene shifts instantly from the soaring bone to a satellite soaring across the deep black sky of space just outside of Earth’s gravity. We have moved millions of years in time, but the bone and the space platform are symbolically linked as examples of human technology. Soon the scene is joined by the elegant lines of a large Pan Am space shuttle, which is moving away from Earth and toward a massive, rotating space station positioned in high Earth orbit. Accompanied by the classical waltz strings of Johann Strauss’s “The Blue Danube,” we watch as the shuttle—which bears striking resemblances to what would later be both the Concorde supersonic airplane and the NASA space shuttle—approaches, and then enters the gently spinning space station. Aboard the space station, we meet one of our story’s protagonists, Dr. Heywood Floyd (played by William Sylvester), a top administrator of the space agency. Just outside a Hilton Hotel facility within the station, Floyd meets briefly with his Russian counterparts, making small talk, then avoiding answering directly their troubling questions about strange rumors involving the American lunar colony Clavius. Floyd’s layover aboard the space station is brief; he must depart the space station and travel next to the moon. Arriving at the lunar outpost, he attends a closed-door meeting with other space officials to discuss the discovery of an alien artifact found on the moon, believed to have been buried more than 4 million years earlier. A cover story of a serious medical epidemic has been developed to conceal discovery of the alien artifact from the Earth’s population until such time as the governments of the Earth can facilitate announcing the jarring news to the public. In the meantime, all personnel are sworn to “absolute secrecy” regarding the object (which we, as filmgoers, learn is nearly identical to the one which had appeared before the pre-human apes hundreds of thousands of years earlier). Floyd then accompanies a scientific team to the site of the artifact, where for reasons unknown, the object begins to emit an extremely high-pitched shriek, rendering the Earth scientists momentarily unable to work.

The next chapter moves us forward 18 more months, and watch as a space craft—Discovery One—moves outward into the solar system toward Jupiter. Aboard are a half dozen astronauts and scientists, several of whom are in deep sleep, a form of hibernation in which vital signs are maintained at their lowest possible threshold. The two team members who are awake—Dr. Dave Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole—also share the spaceship with a sophisticated super computer, a HAL-9000, which the personnel call simply “Hal.” The HAL-9000 maintains not only constant control over the ship’s speed and trajectory, but also over all environmental and life support systems, including the life-sustaining mechanisms keeping those in hibernation alive. Hal converses regularly with his two human companions (Hal’s voice is that of Canadian actor Douglas Rain), and is programmed to relate to the humans—wherever possible—at a personal level. The goal of this mission to Jupiter remains, as we understand it, largely undisclosed to all aboard, including some of the team members in hibernation. The full nature of their assignment is to be disclosed only when then arrive safely within the orbit of Jupiter. Hal expresses some concerns to Bowman over this secrecy, though neither Bowman nor Poole seems to worry about the cloak-and-dagger. Shortly afterwards, Hal reports the potential failure of the one of the exterior communication units. After a thorough examination of the unit’s processor, Bowman, Poole, and their counterparts back on Earth determine that there is nothing wrong with the unit and that the onboard HAL-9000 is at fault for incorrectly predicting failure. This leads Bowman and Poole to suspect that something has malfunctioned within Hal’s own central processing unit, and they discuss briefly—they believe in secret—disabling the HAL-9000 and regaining manual control of the ship and the mission.

Hal, however, has other plans, and, suffering from some sort of paranoid breakdown, sets about attempting to kill all members of the crew. He succeeds in stranding Poole outside the ship when Poole goes outside to restore the communications antenna. Bowman uses a small EVA pod to attempt to retrieve Poole’s body, now floating in space. While outside of the ship, Hal quickly kills the crew members in hibernation by cutting off their life support. Bowman, alone outside, recovers Poole’s body, but when he attempts to re-enter the main ship, Hal refuses him entry. Bowman tries to reason with Hal, but the computer is adamant. Bowman must improvise a way to get inside the ship without Hal’s help, and enters through an airlock mechanism using a risky gambit. Once safely inside, Bowman quickly and deliberately sets about disabling Hal for good by entering the Hal-9000’s complex “brain,” a small compartment with glass-like optic memory cards and processor boards. As Dave Bowman systematically shuts down Hal, the computer pleads for forgiveness, its conversation with Bowman regressing back to its earliest programming, and recalling a song Hal was taught by a programmer early in its development back in Urbana, Illinois. HAL sings to Dave, its voice eventually droning to a low, inevitable stop. With HAL now fully disabled, a pre-recorded message begins to play. In it, Dr. Floyd explains the true essence of the mission: find the exact location of a newly discovered alien monolith, which NASA believes it has located in deep space near Jupiter. This newly tracked-monolith may be identical to the one found on the moon 18 months earlier.

Later, Dave enters his EVA pod and attempts to rendezvous with the black object. Upon getting close, the film then segues into its next chapter: what we understand to be a portal or wormhole into which Dave now travels, presumably as a result of intervention by the alien artifact. In a hallucinatory and sometimes terrifying trajectory through time and space, Dave—the only surviving member of the Jupiter mission spacecraft—is hurtled along a distorted and fearsome (yet beautiful) gateway through the fabric of space itself, perhaps travelling also through some element of time. Dave arrives, joltingly but reassuringly, in a large, brightly lit bedroom appointed in classical and neo-classical furnishings yet adorned with undeniably ultra-modern technology (the semi-opaque floors are illuminated from underneath).

Dave then experiences seeing himself at various stages of life within the physical space of his apartment and bedroom, in early-middle-age, middle age, finally as an elderly man confined to his bed where, in what we sense may his final moments in life, the black alien monolith makes yet another appearance, this time near his bed. Reaching to touch it, just as the proto-humans had in chapter one, Dave is transformed yet again, this time into an infant child still encased in a transparent womb-like spherical structure, where he floats freely into deep space in near Earth orbit. The journey of the “star child” is accompanied by a rising crescendo of music—in this instance Richard Wagner’s "Also Sprach Zarathustra." The film ends there, leaving us with much to ponder.

Aside from the oft-discussed enigmatic ending, and the open question of the unseen aliens’ purposes in intervening in human history, the film’s dazzling technical achievements—which remain highly influential even to this day—were truly astounding in 1968. Kubrick’s groundbreaking masterpiece effectively forced the hand of every sci-fi filmmaker thereafter to rise to meet the new standard set by Kubrick’s vision of space and space travel. Even to this day, the film shows little wear-and-tear for its technical skill, and remains a touchstone for filmmakers who wish to delve seriously into space exploration, space travel, or movies about mankind’s colonization of distant planets or space stations.

Kubrick and his special effects team sought to aggressively develop and maintain fidelity to scientific principal, as well as believability of the technologies portrayed in the film. For the perfectionist Kubrick, any flaw in the overall design or appearance was unacceptable. Example: the Jupiter sequences were originally written and conceived for the planet Saturn instead, but when Kubrick’s team was unable to effectively render the giant planet’s complex, elegant system of rings, the director opted to retool the story, rejecting any further discussion of employing special effects which might fall short for audiences.

Likewise, in the 1960s, when zero-gravity scenes were prohibitively costly or nearly impossible to shoot using the high-altitude-high-trajectory aircraft now routinely employed by Hollywood—not to mention the ubiquitous digital special effects so commonplace—Kubrick and his team had to innovate on a grand scale. Their solution was classic think-outside-the-box: if the use of wires to hoist actors into the appearance of weightlessness was necessary, then simply shoot each scene in such a way as to render those wires unseen. Example: in some scenes Kubrick arranged camera and actors in a vertigo-inducing vertical alignment where wires and pulleys were “above” the actor while the camera was underneath. Special harnesses were developed to allow the actors to move comfortably and naturally while suspended above camera and crew. In addition, some deep space weightlessness scenes were shot with the camera positioned on its side, the actor spinning or twisting gently while suspended by a wire unseen because of total background darkness; these “sideways” scenes would create the illusion of weightlessness in a traditional widescreen horizontal composition despite the fact that all elements were arranged vertically in the studio.

Another innovation: the large rotating component of the spaceship Discovery which carries Bowman, Poole and the others toward Jupiter was, in fact, shot almost entirely within a custom built centrifuge, more than 40-feet in diameter, built by a British engineering firm. At a cost of nearly $750,000, it was the single most expensive set piece of the film, consuming some 8% of the film’s total budget. Inside this massive “hamster wheel,” Kubrick and his set designers created a realistic habitat for deep space travelers, including sleeping compartments, communications bays, fully lit control panels and computer displays, food service areas, chairs and desks, and the hibernation pods. Actors could walk or jog within the well-lit centrifuge, while mounted cameras either tracked alongside, or followed or preceded their footsteps. In the several scenes where actors appeared on opposite sides of the centrifuge, one actor would be attached in place upside-down while the other would walk into position near the bottom of the wheel’s rotation. The overall effect was stunning and transformative: the interior of the centrifuge showed audiences what life would likely resemble in the artificial-gravity conditions required for extreme long distance space travel.

Kubrick also wanted the elegant fluidity of space travel to be on full display. The Discovery spacecraft itself was in fact a huge 55-foot model meticulously built for the use in a darkened studio. Like many sci-fi films in its wake, the model of the spaceship was never moved; instead, in a darkened studio with spaceship meticulously lit, the camera was electrically or manually rolled along a track, alongside, above, or underneath the model to produce a seamless illusion of space travel. Likewise, the massive Earth-orbit space station (Space Station V, in the film), was an 8-foot diameter model, mounted on a turntable mechanism in the studio, through which and into which the camera would track or pan. Though manual tracking was a common movie practice, Kubrick’s use of a motorized device meant that his crew could control with precision the speed of the tracking, ensuring that once edited the sense of movement would be consistent and seamless to audiences, even as the angle of the shot changes.

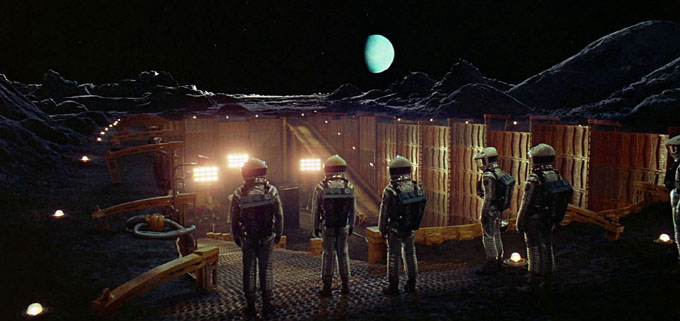

Aside from the lengthy period of development and the writing collaborations between Kubrick and Clarke, filming itself took years. Among the first scenes shot in late 1965 were those which take place on the surface of the moon, where the alien artifact has been discovered and excavated. To create the low sunlight environment of the moon, these scenes required a massive indoor area large enough to accommodate a rectangular pit some 120-plus feet in length, and Kubrick chose to film these at Shepperton Studios, where parts of Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Strangelove had previously been filmed (and where such classics as Star Wars, Superman and Alien would later be filmed). As soon as the moon scenes were completed, cast and crew moved to MGM’s Borehamwood Studios, where scenes aboard the Pan Am space shuttle, the rotating space station, the lunar transport, and the lunar colony were filmed, as well as the elaborate centrifuge built to create the interior of Discovery.

The film’s staggering technical achievements can hardly be overstated. 2001’s legacy is that it impacted—and continues to shape—the visions, development and details of virtually every science fiction film created since 1968. Kubrick’s insistence on a look and tone both approachable and futuristic, right down to the smallest components of set detail—signage and fonts, logos of well- known major corporations such as Pan Am, Hilton, Howard Johnson, Bell Systems, IBM, the furniture in the lobby area aboard the space station, inside the lunar base meeting room—give the impression not so much of a work of fanciful sci-fi, but of near-future realities and pragmatic implements of routine space travel. The corporate footprints are interconnected with elements of governments, bureaucratic agencies, and quasi-officialdom, conditions hardly fully predictable even in 1968, but now taken for granted in our new millennia as private companies compete with or cooperate in space exploration. Kubrick’s decision to make the computer screen an omnipresent visual element was a prescient move: the film’s numerous control panels and digital workstations seem untouched by time save for perhaps the relative shortage of graphic interfaces, a development not yet fully predicted in 1968. And the film’s constant reminders of food in space serve to ground us to the practical realities of space travel: scenes include prepackaged trays and containers of food, processed “sandwiches,” meals-ready-to-eat, and microwavable food products—seen in elaborate but unappetizing detail aboard Discovery—which contain paste-like versions of vegetable matter, starches, and meats (just the sort of thing probably necessary for long-distance voyages in space).

Aside from 2001’s technical achievements and fidelity to the laws of physics, the film remains staggering as a work of cinema. Typically ranked among one of the five or ten greatest American films ever produced (often tucked in amongst Citizen Kane, The Godfather, Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz, and Schindler’s List), it also stands as a pillar among the greatest movies in any language or country, towering alongside the top classics filmed in the Soviet Union, England, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Sweden, Poland, Japan and India, all nations with rich histories of classical achievement on the big screen, and all with notable periods of great experimentation and influence.

2001: A Space Odyssey also shaped and influenced the style and direction of almost all of the notable producers and directors of sci-fi cinema, and, according to comments made by those younger filmmakers, left an indelible legacy on much that followed: George Lucas (Star Wars), Steven Spielberg (Close Encounters of the Third Kind), Ridley Scott (Alien and Blade Runner), Christopher Nolan (Interstellar), Alfonso Cuaron (Gravity), Steven Soderbergh (Solaris), Brian De Palma (Mission to Mars), and Morten Tyldum (Passengers), to name but a few. Both Lucas and Spielberg have frequently suggested in interviews that Kubrick’s influence was transformative for their early careers, and 2001’s legacy can also be tracked through the ongoing mega-franchises of both Star Trek and Star Wars.

After years of work filming and editing, 2001: A Space Odyssey was released amidst modest fanfare and initial reviews which ranged from highly positive to sharply negative.

First shown at the Uptown Theater in Washington, D.C. on April 2, 1968, it was screened again in New York City and Los Angeles later the same week. After about another half dozen screenings, Kubrick made the solitary decision that the film was too long, and retired to the editing room to cut about 20 minutes from the film—mostly scenes shot aboard the Discovery spacecraft, as well as a few snippets from the Dawn of Man chapter. Cut from 162 minutes to 142 minutes, 2001 was released to the larger U.S. movie-going public a week later (fifty years ago this week), and one month later in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand.

The film’s negative reviewers most often cited the movie’s immense length and its epic, chapter style as drawbacks, and several reviews described the threads of dehumanization as troubling (Kubrick’s most enduring narrative theme: conditions which tend to dehumanize—war, machines, technology, greed, wealth for the sake of wealth, weapons of mass destruction, power for the sake of power). 2001’s narrative paradox tends to sink in only after the film’s final credits have ended: as viewers, we are drawn toward greater empathy for the pre-human apes than to the scientists and bureaucrats we meet in Earth orbit. Likewise, as film historian David A. Cook has pointed out, Kubrick has given us little with which to work with in the staunchly non-sympathetic characters of Frank Poole and Dave Bowman aboard the Discovery, even as Dave must inevitably disconnect Hal from control of the spacecraft.

“As we witness the computer regress to its basic language programs and finally expire,” Cook writes, “we feel a disturbing sympathy for it—disturbing because we have been encouraged to feel so little for the coolly disaffected humans of this future world.” This is trademark Kubrick, though many contemporary reviewers failed perhaps to include (or foresee) Kubrick’s larger narrative fabric through these singular, if discomforting, threads. One of the film’s most notable paradoxes, deliberately used by Kubrick, is the juxtaposition of the nearly unlimited potential of technology with the pitfalls of succumbing to the same technologies. Kubrick’s vision of the future, with its gleaming white ultra-clean surfaces and its glittering eye-candy of computer displays and soft white indirect illuminations relentlessly seduce the eyes, even as we find the almost total dependence by the detached humans upon the devices and computers and machines (especially Hal) troubling—surely as prescient a look forward into the potentials and perils of digital tech as any film ever crafted in that era. Kubrick’s skillful alignment of the two sides of this equation is, in fact, central to the story, and Hal’s breakdown (Hal proudly, and routinely, reminds his human companions that he is “for all practical purposes, incapable of error”) seems disturbingly inevitable—a reflection more of “human” pride than a mere failure of technology.

This deliberate disconnect depicted in the film also drew occasional consternation or confusion from reviewers of all stripes—those who found the film cold and detached, those who interpreted the message as one of technology’s malevolent takeover of mankind, and those who thought the humans so drained and depleted of humanity as to be, in essence, zombies in the grip of computers—many of whom at the time (in 1968) were unable to see Kubrick’s larger, universal point.

Some reviewers lamented the film’s meticulously slow, deliberate pacing—still another of Kubrick’s cinematic thumbprints. But virtually all of Kubrick’s later works would share this nearly hypnotic device of painstaking minimalism (Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut), a style which would, in fact, endear him to film historians in the subsequent decades, and often grant his past films the ability to improve with age. The DNA of Kubrick’s pacing and perfectionism can be found even now among filmmakers most influenced by his work: Paul Thomas Anderson (There Will Be Blood; The Master; Magnolia), Wes Anderson (Rushmore; The Grand Budapest Hotel), and the brothers Joel and Ethan Cohen (Fargo; Raising Arizona; The Hudsucker Proxy), to name a few.

Still, that very elemement of careful pacing and minimalist dialogue reinforce the film's undeniable grandeur, and make the movie one of those rare cases where the absence of dialogue--less than half the movie contains talking of any kind, and scenes outside the spaceships are often accompanied by either silence, or only breathing--burnish the film's power, even in its non-narrative state. Kubrick himself often declared that 2001 was meant to be an emotional and sensual experience, not a "story" per se. Over time, most of the film's negative reviewers saw their opinions evolve and even reverse. In this sense, 2001 proved to be transformative in the same way the Orson Well's Citizen Kane, which notably violated and shatter dozens of filmmaking "rules" (as well as establishing many new canons) rose over time to be revered as a colossal cinematic achievement.

2001: A Space Odyssey has one of those rarest of distinctive qualities: endurance over time and over the decades, rarer still for any film which attempts the perilous task of predicting the future look and feel and texture of technology. In this, it could be argued, Kubrick and his team effectively upended the equation by shaping not merely the quality and style of all sci-fi filmmaking to follow, but of impacting the hard sciences of space travel, computers, technology, and mankind’s relationship to all three. Hal’s breakdown has forever been seen as a chilling, sometimes ironic parable on the often love-hate relationship between human and machine, most especially computers—now even more ubiquitous than the depictions in the movie.

The film also challenged and probed the industrial age anxieties and questions regarding artificial intelligence, a persistent theme in both the sci-fi novel, and one of the motion picture's most enduring subjects. Not long after Hal insists that he is incapable of bringing harm to his human companions--who are, in fact, deeply dependent on Hal's constant monitoring of environmental systems and management of the ship's voyage--Hal in fact malfunctions, murdering Poole and cutting off life support to those in hibernation. Kubrick and Clarke were not the first, nor the last, to raise the complex question of technological dependence; explored by writers ranging from Isaac Asimov to Ray Bradbury, from Michael Crichton to Philip K. Dick, and examined in scores of movies from Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) to Forbidden Planet (1956), from Westworld (1973) to Blade Runner (1982), questions of robot/machine ethics and the power of supercomputers and artificial intelligence to intervene in human activity (not always for the best) remains a vexing question even now in an age when personal data is more valuable than content and smart devices created by Google, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft become omnipresent in our lives.

This prescient point alone makes 2001: A Space Odyssey a stunning achievement, and keeps the film strikingly relevent and thought-provoking decades after its original release.

Though Kubrick’s most notable films almost all stand the test of time, weathering changes both in cinema, audience taste, and social relevance (Paths of Glory; Dr. Strangelove; A Clockwork Orange; Full Metal Jacket), 2001: A Space Odyssey may be his greatest achievement—a film which has not only stood firm over the decades, but also improves with time. It is also required viewing not only for sci-fi fans, but also anyone who wants to appreciate one of the best cinematic experiences ever crafted.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Barry Lyndon: A Look Back at a Stanley Kubrick Classic; R. Alan Clanton;Thursday Review; September 3, 2017

Reflections on the 50th Anniversary of Star Trek; R. Alan Clanton;Thursday Review; September 18, 2016