By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review Editor

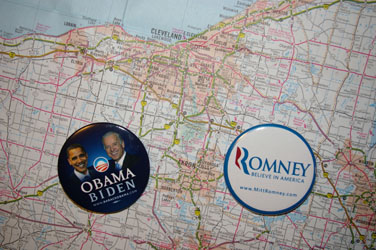

October 29, 2012: Hardly any of the major news organizations—even those with a decidedly liberal tilt, even those with an overtly conservative viewpoint—are willing any longer to make an outright prediction about this election. Most polls now show the race having already tightened to the point of a virtual tie. Battleground states that were once leaning tentatively one way or the other—Florida for example, as well as Nevada—are now approaching dead heat status for both President Obama and challenger Mitt Romney. A few polls place Romney slightly ahead, a few now show Obama with a marginal lead.

As a result, the candidates and their surrogates are campaigning at a feverish pace, seeking to push or skew the numbers by even a fraction of a percentage point, spending sometimes as little as 80 minutes in one state before climbing aboard a plane to fly to the next critical hot spot. The distance to the finish line is no longer being measured in months, weeks or days, but in hours and even minutes. Ohio has become so critical to the strategy of both camps that television viewers in places like Cincinnati, Cleveland and Dayton are being subjected to more political TV ads per hour than ever before in history, with Florida, Colorado and Iowa not far behind. Indeed, despite my skepticism earlier this season, we may hit that billion and a half dollar mark for total campaign spending before Election Day.

Florida, with 29 electoral votes, is now officially considered too close to call, at least according to a new CNN/ORC poll released Monday which shows Mitt Romney leading the President by one percentage point, 50 to 49. Both campaigns will shower the Sunshine State with many more millions in advertising over the next seven days, and even TV viewers in adjoining or overlapping broadcast markets—south Alabama and south Georgia, both safe states for Romney—must endure the seemingly endless barrage of ads meant to convert the handful of undecided voters in places like Pensacola, Panama City, Tallahassee and Jacksonville.

Let’s be clear: in close elections like this one anything can happen. The Electoral College map has become a place of treachery and danger for both sides, especially now that some unaligned and undecided voters have begun to make their decisions. There are even a few models which show that Americans may wake up on Wednesday, November 7 to an electoral tie of 269 to 269, in which case the presidency is decided in the House of Representatives, though this strange scenario is unlikely.

The debates settled little, save for establishing Mitt Romney’s bona fides as being made of presidential timber, which for the GOP in their difficult post-convention days, was enough. In the second debate—as in the vice presidential match-up—the candidates, and especially the President—substituted alpha male aggression and rudeness for facts or policy specifics. Only Paul Ryan remained as the gentleman among the four candidates. The last debate, on foreign policy, demonstrated little as well. More subdued, Romney’s tact was to convert many of the international arguments back toward economic policy—as was expected—and the President used the venue almost exclusively to needle Romney on past statements and remarks, in some cases as far back as 20 years prior. Romney also became the moderate and the conciliator on many foreign policy issues, moving slyly—at least according to some in the mainstream press—somewhere to Obama’s left, an media interpretation not entirely accurate since Romney had never campaigned as a tough-guy interventionist, either in this election cycle nor in 2007-2008.

Unlike Candy Crowley’s intervention in the third and most contentious debate—the match-up which seemed to project the notion of two candidates who do not very much like each other—Bob Scheiffer’s more detached and scrupulously unaligned style gave both candidates the opportunity to clarify and sharpen their positions. Romney, as we have seen, used the opening to become a centrist and a peacemaker on foreign policy, deploying the same methodology once used by candidate Ronald Reagan back in 1980 and showing himself to be reasonable and measured in the use of force. In response, the President deployed sarcasm, belittled the former governor’s record, and even badgered Romney on issues where they disagreed.

Analysts with predispositions toward the Democrats or the President, using the same criteria applied after the Biden versus Ryan match-up, immediately claimed it was a smashing victory for Obama. Dismissive sarcasm always makes for a better sound bite than a dry roll-out of the facts. Many ostensibly neutral reporters in the media declared Obama the winner, on points at least, but it had little effect on the immediate aftermath: post-debate snapshot surveys showed close numbers, with Obama judged the winner by only a few percentage points more than those who thought Romney had won. Liberal analysts pounced on this as evidence of skullduggery or rank partisanship a national polling. But within days Romney still managed to close the fractional gap and even pull slightly ahead depending on which poll one looked at.

This gave rise to still more complaints from Democrats and left-of-center interest groups that the obsession with poll numbers and numerical trends creates a distraction by likening the sacred democratic processes to a horse race or a boxing match. Style displaces substance; process overshadows policy. We heard much the same discussion in the immediate aftermath of the first debate, that moment of critical mass when the momentum seemed to begin to shift toward Romney.

Crowley’s multiple interventions during the third debate—the Town Hall format—gave rise to a predictable sideshow conversation among conservative opinion-makers and right-tilting blogs (on Fox News, the matter became central to the narrative) about a general media tilt toward Obama. That Crowley had weighed-in on whether the President had used the words “terrorist attack” in a press conference after the violence and murders in Benghazi was seen as evidence of not merely her pre-dispositions politically, but also her impulse to get it right for Democrats on an issue perceived as making the President look vulnerable.

In truth, neither candidate was being completely forthright on the specifics: Romney ignored that Obama had in fact used the words, but in a somewhat oblique reference which many could have interpreted as unrelated to the precise events at the embassy. Crowley chose to be the referee, and she ruled it in favor of the President, rather than taking a more measured middle path between the two combatants. But this proved to be only a brief vindication for the President, as the news for the State Department and the Obama administration got worse, with continuing revelations of communication failures, non-responsiveness and outright incompetence along the official chain-of-command. This has given Romney and his strategists the opportunity to claim the high ground on Middle East policy. Again, echoes of 1980 and the complex, high stakes processes surrounding the Americans held hostage in Tehran. For the first time since the conventions, Democrats feel some degree of vulnerability on foreign policy, the issue only recently touted as Obama’s strongest counter measure against a Romney surge.

In short: the debates, widely discussed and anticipated since even before the Republicans convened in Tampa, were seen as that place on the obstacle course where Romney would no doubt fall flat or stumble outright. Few in the mainstream press saw Romney as a come-from-behind kind of guy in these contests, and a heavily insulated and disconnect White House felt little need for preparation in advance of the first debate at Denver University. Unfortunately for Obama, Romney’s decisive win in Denver set the tone for the rest of October, and subsequent debates have done little to alter the momentum.

Still, there are seven full days remaining. If one factors in a brief stump hiatus on both sides to accommodate Hurricane Sandy and its ferocious aftereffects—both campaigns suspended field operations through at least Wednesday morning—that leaves only six days for the candidates to sell their message to those last few truly undecided voters. Mistakes can be made, and probably will under such pressures. The President shrewdly and wisely took the step of cancelling campaign events in Florida to fly back immediately to Washington, a reasonable step for logistical purposes—the President needs to be in the White House to take command of the federal response to any unfolding multi-state disaster—as well as for reasons of political theater. The President, after all, needs to behave presidentially. Romney was prudent to act accordingly.

Campaigning in Fernandina Beach, Florida, vice presidential contender Paul Ryan asked that campaign workers along the east coast in Virginia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and other states divert their volunteer energies toward disaster relief.

In the meantime, voters and television viewers in the most hotly contested states away from the full force of Sandy can expect to continue to endure carpet-bombing in the form of political advertising. That means Iowa, Colorado, Ohio and especially Florida.

[there will be more on our continuing series about media balance in the next edition of Road Show]