By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review Editor

Though the consensus is that Thursday’s vice-presidential debate in Kentucky settled very little, except for channeling the energy of certain base elements of both parties, there is a clear sense that the narrative for this election has begun to shift in Mitt Romney’s favor, and that support for President Obama—once holding a solid five to seven point lead in most surveys—has begun to slip back into a familiar numerical template.

The much-discussed and often over-played story of the independent and unaligned voter may be reaching closure, especially now that the mythical creature known as the “undecided” American begins to take a clearer, most recognizable face—that of the Reagan Democrat.

So Thursday’s debate between vice-president Joe Biden and his Republican challenger Paul Ryan served to clarify many things for many voters, one of them being that the factors in this election may more closely resemble the conditions of 1980 than most analysts were willing to previously accept.

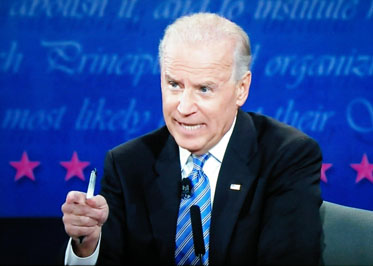

Shortly after the debate began, it, it was very clear that neither man was willing to give ground, and this was not a surprise: no quarter was asked, none was expected, and indeed under the focused guidance of Martha Raddatz the debate raged as contentiously as possible without someone getting punched in the nose or someone’s eye getting gouged out. There was the more-or-less continuous distraction of Joe Biden’s antics—the eye rolling, the snorting, the laughing out loud, the innumerable interruptions—which led some on the Left to suggest Biden “won.” But the exchange did produce a surprisingly large volume of substance, in truth far more than we saw in the first debate between the President Obama and Mitt Romney. And in Thursday night’s case, we have learned again that substance matters—especially when it comes to the economy.

With new polling showing Ohio back in play for the Republicans, and with even newer polls placing Mitt Romney ahead of Barack Obama in Florida, the race for the White House now appears to be tightening further—and there is evidence of a shift nationally in favor of the GOP. Despite an NBC News/Wall Street Journalpoll showing Florida a virtual tie between the two candidates, a more recent survey conducted by The Tampa Bay Times/Miami Herald newspaper group shows Romney with a seven point lead over President Obama in the Sunshine State, the widest margin in many months for Romney.

Further, additional poll numbers released by various news agencies this weekend show measurable gains for Romney in a variety of demographic shapes and forms, the most dramatic being the numbers produced by NBC News which now show Obama an Romney in a dead heat among women voters.

For the Democrats and the Obama strategists, this is a particularly troubling development. Other than African-Americans, Obama has had no stronger demographic support than women voters. The gender gap was in fact so profound that only weeks ago the disparity between male support for Romney and female support made it seem unlikely that Romney could ever recapture the votes of women, many of whom in the 1980s and early 90s helped to shift the electoral template toward the GOP.

Women voters, especially white women, have tended in contemporary times to be more independent and somewhat less ideological than their male counterparts. Particularly pragmatic on issues of the economy—joblessness, inflation, taxes, health costs—women view candidates and parties on the traction of their proposals and potential for real world results. Ronald Reagan understood this clearly in 1980, and in his famous debate close on the eve of his Election Day challenge to Jimmy Carter, Reagan’s question of are you better off than you were four years ago could be said to have resonated among women far more than it did among male voters. Four years later, facing a challenge from Democrat Walter Mondale, Reagan was able to easily avoid Carter’s predicament, for the economy was better off.

By direct comparison, Romney’s smashing debate performance—and Obama’s weak showing—may have played a key role in redirecting female voters, especially those whose political loyalties reside less with party labels or the loose terms conservative or liberal, but more with authenticity, trustworthiness and the potential for genuine results. Like Ronald Reagan 32 years earlier, Romney not only showed himself to be presidential, he also largely erased the fear factor among women uncertain or unsure of Romney’s authenticity or veracity on economic matters.

Under normal circumstances the vice presidential debate would have had little impact, and indeed the debate seems to have inflamed the conversation among the political partisans far more than unaligned or independent voters. But because there were no truly dramatic moments, and because no one was seen as having a decisive win (CNN’s polling showed that 48% thought Ryan had won, as compared to 44% who gave the nod to Biden), momentum from the presidential debate in Denver still carries the day.

This of course puts even more pressure of the two men at the top of the ticket for this Tuesday’s debate rematch at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York. We can be certain the President Obama has been thoroughly coached to go on the offensive in this week’s match-up with Romney.

In the meantime, some of the most substantive and contentious aspects of the VP debate have led the media chatter into closer examinations of two themes: taxes, and Libya.

Biden and Ryan argued bitterly over both, and in the case of the issue of security for diplomatic personal in Benghazi, the vice president—in an attempt to explain a catastrophe which is being largely blamed on the Obama administration and the State Department—became entangled in his own apparent mishandling of the facts. In the debate Ryan cited the recent violence across the Islamic world as an indication of a haphazard and failing foreign policy. Biden responded by saying that there were no official requests for additional security in Libya. But as it turns out, requests were made officially for better security and beefed up security at the diplomatic compound and other locations in Libya. This put Paul Ryan’s analysis on the right side of the dispute, and Romney wasted little time using this fact as a blunt weapon on the campaign trail at appearances in Florida and Virginia.

More complicated, however, are the arcane and downright byzantine matters of taxes and tax cuts. Romney, now within a month of the general election, continues to modify and moderate his position on taxation and budgets—shaping and honing his message along the campaign trail to best channel voter energy toward what he sees as a more proactive plan for economic stimulation and jobs growth. Romney—despite the accusations that as governor he was either too liberal or too conservative—in fact governed as a conservative surrounded by liberals, still managing to create a balanced budget andoffer universal health care. Not an easy task by any criteria, and had it not been for the fact that Romney was forced during the primaries to disavow Romneycare, he might have been empowered to use this weapon on the campaign trail as evidence of his obvious skill at balancing the complex factors of a large economy while still producing a budget surplus.

Ryan, the true fiscal conservative, and more of a purist than Romney, sees that all things are possible with sound management—lower taxes, less government spending, a balanced budget, plus a growing economy. Both John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan had achieved the same model of success. Biden scoffed at this, and during the VP debate the vice president essentially accused Ryan of skipping math class the day the taught math in school. Biden suggested that Ryan was trying to defend impossible arithmetic by suggesting that budget-cutting coupled with massive tax cuts won’t lead to more deficit spending. Ryan, avoiding specifics, nevertheless disagreed.

And this takes us again back to the frequent comparisons to the election of 1980, when candidate Reagan was accused—among other things—of engaging in voodoo economics (and it was Republican George H.W. Bush who first used the infamous term). Ryan, the numbers wonk and budget policy guru, held his ground throughout the debate, insisting that the Romney-Ryan plan would create jobs and give Americans a balanced budget. Biden called that malarkey.

Still, in an election in which the larger backdrop is an anemic economy, the question for many voters may still come down to jobs. All Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan have to do is convince uncertain Americans that what the GOP ticket offers is economic certainty.