By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review Editor

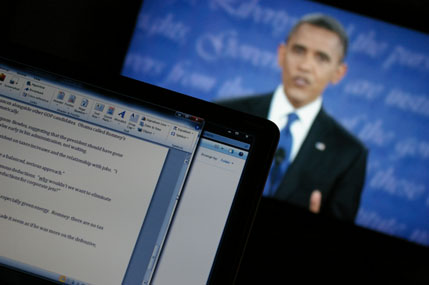

Sometimes it just feels right when the herd gets things wrong. Last night’s debate between President Barack Obama his Republican challenger Mitt Romney is one of those striking moments when we get to see a thousand reporters and analysts eat their own words, and still have room for (their just) desserts.

Make no mistake: by 10:30 p.m. Eastern Time the last ten days of pre-debate hyperbole suddenly seemed like an eternity of wasted effort and misdirected energy. Romney had not merely met that traditional challenger’s expectation of looking presidential on the stage—an easy enough task by simply showing up—but the former governor also managed within the first 15 minutes to exceed expectations. By 25 minutes into the debate he had forced the President into his own corner, and by 35 minutes the fight was over.

It wasn’t even close, and no amount of spin by David Plouffe or other top Obama surrogates could change that nearly uniform conclusion.

There were, of course, no major mistakes, no gaffes, and no major foul-ups last night in Denver. No one placed Poland on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain, no one imprudently compared themselves to John F. Kennedy, and no one glanced impatiently at their watch or snorted contemptuously into their wireless microphone.

That the debate concluded free of misfires and pratfalls should have come as no great surprise to anyone, for no two candidates in American history possess as much total debate experience as President Obama and Mitt Romney. Obama, after all, had stood toe-to-toe with some of the best political litigators in the business, including John Edwards and Hillary Clinton, and he had emerged from those 2008 contests better for the wear. Romney outlasted everyone but John McCain in 2008, and then survived the recent cycle of GOP forums which totaled nearly 30 beginning in May of last year and concluding early this spring.

Never have two such polished and self-assured individuals shared the debate stage. Nevertheless, last night’s widely-watched debate in Denver seemed to show us—perhaps temporarily (you could hear the wishful thinking in some reporter’s voices and tone afterward)—a Romney now in charge of the conversation, and a president unprepared for the task of defending his record.

President Obama shifted on his heels, seemed at times distracted, delivered sometimes rambling answers, and spent a lot of time staring down at the podium—a mixed bag of body language misfires that stood in contrast to Romney’s calm, poise and balance. Even the president’s closing remarks—that famously defining opportunity to sum up the case for re-election—fell flat. The president sounded almost pleading when he asked Americans to reward him with four more years.

Though the President had ample opportunity to control the space and the pace in their match-up in Denver, Mitt Romney won this 15 round match-up easily. To extend the boxing imagery further, there were no knockout punches, but on points the governor won it in a unanimous decision.

Romney’s only problem, minor to be sure, came in the closing 20-minute stretch as he sensed clear victory: his aggression, though checked by his carefully modulated body language, spilled into his voice which seemed occasionally overly-excited. The president was on his heels and Romney wanted to keep him there. But by that point few people were paying close attention to such details. By the 45 minute mark Romney had clearly “won” the debate, by whatever vaguely defined set of criteria one wishes to impose on such contests.

Though he displayed his usual coolness and unflappability, the president nevertheless seemed at times distracted and unsteady, at other times strangely unprepared. In sharp contrast, Romney seemed in command of his facts, as well as able to quickly respond to the president’s bean-balls about tax cuts and the super-wealthy.

Obama never once mentioned Romney’s now over-played 47% remarks, never referenced Bain Capital, and only once mentioned Romney’s huge proposed defense spending increases—and then only in relation to the issue of deficits. Romney was confident and prepared with his bullet point list proposals on everything from jobs to health care, and when moderator Jim Lehrer gave the president a clear opportunity to strike at the heart of the appropriate role of government—Obama floundered: on improving health care, Obama had cited the example of the Cleveland Clinic. Romney quickly pounced—pointing out that the touted success story in Cleveland was, after all, a private sector solution.

To be sure, there will be a close examination of Romney’s words about taxes and revenues and deficits, all matters of great import to Americans and especially those reporters seeking to pin the governor down on his sometimes vague proposals. Indeed, the president’s own attempts to force Romney into specifics failed largely because of the speed and confidence of the governor’s retorts.

But what seemed to stymie the president’s performance the most was Romney’s effective use of jobs creation as the central talking point of any exchange—from medical costs to government regulation, from tax cuts to energy independence (Obama was notably cagey when the talk turned to energy). The former governor had clearly made the decision early in the debate to make jobs the high ground, and he repeatedly brought the conversation back to that.

That the president seemed so profoundly unable or unwilling to meet that discussion head-on is indicative of how quickly the view of this election may change within the next few days.

Granted, there are still four weeks to go before Election Day and much can happen on the ground to change the momentum, but for now at least, Mitt Romney has an opportunity to seize control of the larger narrative.

Of the many debates Americans have experienced or endured over the recent decades, last night’s was a surprisingly substantive exchange—free of mortal gaffes, silly one-liners, wild haymaker swings and the other forms of showmanship so beloved by reporters and analysts, and so seemingly ubiquitous in the age of television sound-bites.

This was good news for voters: having set aside the need for such gamesmanship last night in Denver, these two candidates were willing to engage in a long-overdue dialogue on the issues that most matter to Americans.