By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review Editor

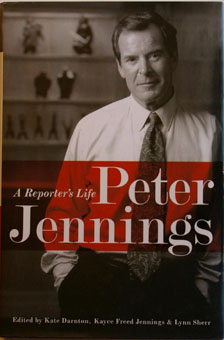

A Reporter’s Life; Peter Jennings; Edited by Kate Darnton,Kayce Freed Jennings and Lynn Sherr; Public Affairs Books. Peter Jennings was once called—joshingly by some, derisively by others—the Boy Anchor. Elevated to the job of principal full time anchor of the fledging ABC News outfit in 1965 while he was still in his tender twenties, he became the youngest news anchorman in TV history, and, as it would turn out, a young man totally unprepared for the task. When his youthful inexperience proved to be an unmitigated catastrophe, he was gently and deftly demoted, then relocated to London, where he served as chief European correspondent for ABC, and where he set about learning to become a serious reporter while the more formidable figure of Frank Reynolds became the face of ABC News.

But Jennings was a tenacious student and a formidable personality. He soon learned the ropes, cutting his teeth on stories ranging from the Middle East to Europe to Vietnam, and when the young Canadian was the only member of the ABC News team attached to the larger ABC Sports contingent assigned to cover the 1972 Olympics in Munich, he found himself thrust directly into one of the most shocking and dramatic stories of violence and terror in modern times. Already an expert on Middle East politics and culture, Jennings provided lucid, balanced reporting from the scene of the hostage crisis where Palestinian terrorists were holding Isaeli athletes at gun point inside the Olympic Village.

A few years later, after another failed experiment, this time with a three-way anchor format—an awkward and logistically complex set-up which included Jennings in Europe, Reynolds in Washington, and Max Robinson in Chicago—Jennings found himself being groomed once again for the top spot at ABC News. Then, in 1983, the venerable Frank Reynolds died of lung cancer. Like many Old School reporters, he had been a chain smoker through nearly his entire journalistic career.

As a result of Reynolds’ untimely death, Peter Jennings was given a second chance; elevated by ABC News president Roone Arledge to the anchor desk. Jennings quickly became iconic, joining the elite club of the so-called "second generation" anchors—Tom Brokaw at NBC, Dan Rather at CBS, each of whom had themselves followed in the footsteps of the larger-than-life figures of David Brinkley, Chet Huntley, and Walter Cronkite. Jennings, a Canadian with only minimal understanding of American politics, had to learn fast—for one of his first major assignments would be to sit in the anchor booth at the Democratic and Republican National Conventions in 1984. Less than 18 months later, he would work at his anchor chair live for over 20 hours on the day of the Challenger explosion, deftly and calmly guiding viewers through the complexities of the tragic disaster. By the end the next year ABC News had moved into first place, and Jennings had established his journalistic bona fides, as well as his place among the pantheon of great TV anchors.

A Reporter’s Life is not the singular work of Jennings or his ghostwriters. Instead, it is a quirky collection of testimonials and recollections by those who knew him and worked with him over his long career. Jennings own words are peppered liberally throughout, but in between are direct quotes and stories from all the others who knew him—Ted Koppel, Sam Donaldson, Gretchen Barbarovic, Dan Rather, Tom Brokaw, Charlie Gibson, Cokie Roberts, Lynn Sherr, Peter Shaw, Dick Ebersole, Bill Blakemore, and dozens of other reporters, producers, writers, editors and colleagues. Each of these voices adds to the process of illuminating Jennings and his career. The book also includes retrospectives of Jennings’ life from luminaries such as Bill Clinton and Condoleezza Rice.

What emerges is the story of a young reporter fascinated with the power of television, as well as a young Canadian who fell in love with the United States. Jennings, who was by his own admission the weakest of the three major late century anchors at the reboot of his career, pushed himself harder and more intensely than Brokaw or Rather; his unvarnished early insecurities made him into a perfectionist and, many would argue, the consummate anchor. Some of his close colleagues—Martha Raddatz and Bob Woodruff, as examples—offer their recollections of Jennings as pushing and prodding continuously for something akin to perfection. Sam Donaldson described Jennings as “very domineering. He was demanding. He was exacting.” Investigative reporter Brian Ross put it this way: “I’ve never had a tougher editor in terms of scripts.”

Combining his suave looks and easy, graceful charm with his determination to get the story right, Jennings eventually reached the top of his profession at the very moment when electronic glitz and sparkle was making the Old School methodologies of TV journalism largely obsolete. These hundreds of vignettes and stories, told by Jennings’ colleagues and friends, show us an anchor and an editor unwilling to compromise simply because the medium had become—itself—the message.